Turkish troubles

Entry to Turkey has been accompanied by a two week hiatus in my biking exploits, on account of technical difficulties.Before then, in Iran, I discovered by the wonders of the web that there was another biker in Tabriz. I soon found a hotel with a BMW R1150GS Adventure parked in its lobby, and Jason wasn't far away. He's travelling the other way, from Holland to Australia, and reckons he's the first American to travel solo in Iran for ten years. We spent a good evening swapping information and maps - all we lacked was a beer to wash it down.

On the way from Tabriz to a town nearer the border, I made a detour to the Urartian site of Bastam. The Urartians are another ancient civilisation of which I'd never heard, prominent around the 8th century BC. Like the fortresses of the Assassins, this one was perched impressively on a sheer rock. My reveries on the antiquity of the walls were brought to an abrupt halt when my subconscious pointed out that I had failed to retrieve my passport from the manager of the hotel when I paid, so I had to head back to Tabriz for another night, with six hours of riding for nothing. You've got to laugh, but I didn't when I woke up to find that my bike had lost almost all compression on the kick-start. For now, it didn't run too badly and at least it was sunny for the first time in a while, so I enjoyed the starkly beautiful trip back towards the border. With my mind already on Turkey, I was pleasantly surprised by the small town of Maku, which is set in a dramatic gorge and afforded a final opportunity for a flurry of Iranian hospitality.

At the border, I knew what to expect from Bernard's crossing, but found to my grief that they were intent on screwing ninety dollars out of me, to his thirty. The idea was that the insurance we had bought on the way in, supposedly valid for the duration of our stay, actually lasted only ten days, so I had over-run by rather more than he had. I couldn't try the usual tactic of sitting it out for a day or two, since I was now on the last day of my visa, so there wasn't any option but to pay. A shame to leave Iran on a sour note. Thankfully entering Turkey without a carnet is no problem, so I didn't have to take a hit on both sides of the border, and was through them both in a mere four hours.

The twin cones of big and little Ararat

A short ride past the spectacular snowy cone of Mount Ararat, of biblical fame, brought me to Doggybiscuit. What shocked me immediately was to see uncovered women. Women with more than faces: women with hair, women with bodies. I hadn't realised just how much a month in Iran could affect what the brain accepts as normal. Another difference was the curious fill-in-the-gaps style of asking all the usual questions: 'My name is...? I am from...?'

My culinary experience of Iran had improved when I realised that, although a dual pricing policy made staying in better hotels prohibitively expensive, this policy was not applied to their restaurants, so they provided a welcome alternative to kebabs. Even in small Doggybiscuit, however, it was clear that Turkey is a gastronomic grade above. Over a breakfast of fresh bread, olives, cheese and honey, with a view of the mountain lit by the early morning sun, I could tell I was going to enjoy Turkey. Lunch was a plate of meze on a terrace by a spectacularly located castle, and as I ate I wondered whether I might have crossed the wrong border by mistake, into paradise rather than Turkey.

A good spot for a castle

However, the harsh realities of an ailing bike soon dispelled any such notions. Fixing it turned into a catalogue of disasters. For reasons that elude me, the engine had in such a short time reached such a state that it needed a re-bore (fortunately I'm carrying an over-sized spare piston). Ironically the damaged cylinder was then involved in a motorbike accident, which involved neither me nor the rest of the bike!

Previously, I had fallen in with a happy-go-lucky couple of guys: Metin, who works at the hotel, and Musa, a would-be campsite owner. Although used to the relaxed approach to timekeeping that is endemic in developing countries, I couldn't understand why they took quite so long over the simplest of missions, until I discovered that they have to stop for a cup of tea whenever they meet anyone they know. In a small town, that happens rather often. Of all the tea-loving peoples I have come across, the Kurds win hands down, and consequently my intake has risen to about fifteen cups a day. They led me, tea stop by tea stop, to the crack mechanic of Doggybiscuit, a deaf-mute with a shortage of fingers but a good line in visual humour. After a couple of days of delays, he indicated that he thought he could do a good job on the repairs. When gestures didn't suffice, communication took the form of a game of Chinese whispers, since nobody who could interpret his signing spoke English.

Things took a turn for the worse when Metin set off on his motorbike with the mechanic and various bits of my bike. They hit a car that pulled out in front of them, which is hardly surprising since they were riding at night with no lights and no front brake (and no motorbike license). Curiously everyone, including the police, agree that it was the fault of the car. Metin was largely unhurt but the mechanic suffered bad bruising and an aggravation of an old back injury. The piston and cylinder went flying but amazingly, once I'd retrieved them from the police (who had impounded them along with the crashed bike), they were undamaged. However, a broken tappet guide from my bike, which was going to be fixed, couldn't be found.

While waiting for the situation to settle, I spent three nights in a Kurdish village at the foot of Mount Ararat, courtesy of Musa and his family, who certainly gave the Iranians a run for their money in terms of hospitality. Despite his trendy appearance, it turns out that he's one of eleven siblings from a subsistence farming background. The village depends largely on sheep; of its working age men, 43 are shepherds and 31 aren't, and their tasty staple meal is home-made sheep's milk cheese on freshly-baked flat bread. The family's home is modest, without running water (but with satellite television!). The village is in a stunning location, next to a lake with the lowest slopes of the mountain on one side and green pastures on the other. At first sight this appeared to be a rural idyll, particularly when we ventured a little way up the mountain to find a shepherd friend among the flocks, and made a camp fire to boil up some tea on the kettle he carried on his donkey.

As you might expect, the idyll was shattered as it became apparent that the village shared the universal problems of countryside living, with the perception by the young of a chronic lack of opportunity. The stifling smallness of the community was indeed very striking as we did the social rounds in the evening, dropping in on neighbours, or on shepherds in their barns, or the grocery store, for cups of tea and the latest sheep gossip.

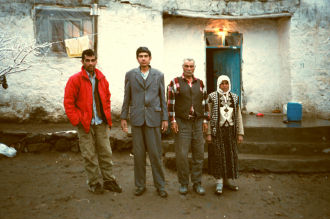

Gradually it also became clear that the family situation wasn't the happiest. Musa lives with his flat-capped father and an assorted complement of relations, including a young woman who kept herself well hidden and whose position was initially unclear. It transpired, much to my surprise (since he pointedly ignored her), that she was Musa's wife. I was told she was pregnant, but I didn't appreciate quite how pregnant until she gave birth to a daughter during my second night there! It was a very matter-of-fact affair, with no midwife or doctor in sight, and I wasn't even aware of it until the morning, despite the fact that it happened only two rooms away!

My Kurdish hosts for a taste of village life

Happy though this event should have been, Musa cruelly declared that he wanted neither his wife nor the child. I later discovered that they had been married only four months which, in a fairly strict Muslim town, rather explains the sequence of events. With his true side revealed, I was happy to return to Doggybiscuit, by now through the snow since spring had lost ground to winter again. Despite the generosity of the family, being a guest becomes a bit wearing after a while, particularly when communication is so difficult, and I felt uneasy being waited on hand and foot by the women, as is the wont of the men here.

Back in town, a couple of days were spent having new and old parts skilfully machined on a massive lathe. With the mechanic still laid up, I was feeling a little frustrated at my predicament, not least because the intrinsic charms of Doggybiscuit are close to nil. I tried taking a bus to Van, having heard a rumour that the recent prohibition on foreign visitors had been lifted - perhaps the Turkish government had decided that it wouldn't need to perform whatever dastardly deed it was planning for the Kurds down there. In any event, I was pleased to make it through the checkpoints without being ejected by the military. Judging from the complete absence of foreigners, others either hadn't been so lucky or hadn't tried it since the end of the war.

Van is situated on a vast, almost marine, eponymous lake, whose far shore is only apparent from the snowy peaks that rise from it, and whose salinity is clear from the sea smell of the air. Despite my lack of independent transport, I was lucky enough to be given breakfast in the home of some friendly Turks, who drove me to the departure point for a boat going to a small island that bears a beautiful and ancient Armenian church. My companions on the boat trip, a Turkish couple on holiday, took up the baton, and I accompanied them to a distant mediaeval Kurdish fortress, before being deposited back in Van. The town's principal attraction is the massive castle that sits atop a ridge by the lake. Like Bastam, this is also of Urartian origin, but differs in that it is largely intact, making it an enormously impressive site. A happy day was spent reading on its walls, with their stupendous views.

On my return to Doggybiscuit, after a few more days of delay and false-starts we took my bike on a truck to the house of the mechanic, who was still immobile. He dragged himself, literally, to his doorstep to supervise the work. I had been tempted to try to fix it myself, but am glad that I didn't since I wouldn't have been able to do nearly such a good job. The work was finished today and, almost to my disbelief, it seems to have been fixed - it now behaves more or less as it should. However, the only meaningful test is the remainder of the trip, so now I just have to see how long it lasts.

Today Paul, also English but heading east on an XT600, arrived in Doggybiscuit, and we met as arranged. Doubtless before long I'll be cursing the touristy coast and package holiday makers, but for now it's good to meet some fellow foreigners occasionally, particularly other overland bikers! Tomorrow I'll head south, overjoyed to be on the move again, inshallah.