The Island Part 3 (This blog was originally posted in June 2011 on Travelpod)

... Continued Part 3.

Our simple relating of what we did on the Isle of Man was never going to be a sufficient explanation of what it was really all about, what we took away from it and how we felt about going back sometime. At first, no matter how we looked at it, the TT was an anachronism; an event that was left over from another time and that had somehow survived like a hidden valley of dinosaurs. Certainly, this event could not be run in Australia, the US, England or almost anywhere else in the developed world. Health and safety concerns aside, so many people having so much fun with so little supervision simply isn't allowed anymore.

Initially, I took the cynical view that the Isle of Man government had allowed the event to continue because it needed the income generated each year. The island's tourism industry was, as far as we could see, on its knees. The cost of transport to the island has made the place uncompetitive when working Britons can buy cheap airfares to someplace sunny and warm for about the same price. There may well be many unique tourism niches open to the island but from our observation little had been done to identify and market them. The result was a rather run-down infrastructure and a treasury thankful for TT fortnight.

But, if this was the extent of our thoughts, it would sell the TT, and all of those who love it, short. The longer we stayed on the island, the more we became aware of and involved with the history of the island and the race. We started to hear the great stories retold and to hear about the champions who conquered the mountain. Their names are legendary: Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini, Stanley Woods, Joey Dunlop, Phil Read. We heard about Frank Walker who raced a Royal Enfield in 1914. He was leading when he had a puncture. After the repair he fell twice in the chase to get back to the lead. When he crossed the finish line he overshot the mark and crashed into a barricade and was posthumously awarded third place by the race committee.

Then there is the story of how the Americans brought their Indian motorcycles to the island. These were machines with proper gearboxes and clutches, multi-cylinder engines and the strength to deal with the immense distances and poor roads of the US. English bikes of the time were generally belt driven. The Indians wiped the floor with the local bikes in a 1st, 2nd and 3rd place humiliation that the locals still make excuses about 100 years later. The winning Indian ridden by Oliver Godfrey was so far ahead they made jokes about his lead for years.

Stanley Woods raced on the island all his life and had 10 TT victories. He lived on the island, became a successful businessman and survived to be 90 years of age. Mike Hailwood returned to the TT after 11 years of retirement and rode a 900 Ducati to victory in the 1978 Senior Race in a feat of riding that is still talked about in hushed tones today.

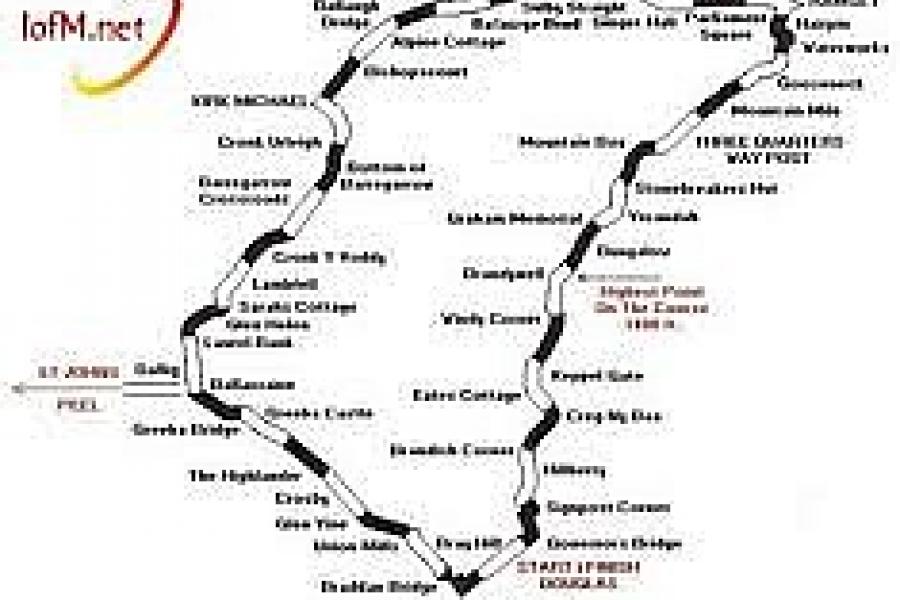

Honda came to the island for the first time in 1959 with a 125cc racer that took sixth place in the lightweight TT race at an average speed of 68.29 miles per hour. Honda had started their race team just to compete in the TT. Today, Hondas dominate the TT races with winning average times over 125 miles per hour. Omobona Tenni raced from 1934 and became the first Italian winner in 1937. And so the stories go on. Each a small addition to the legend of the TT.

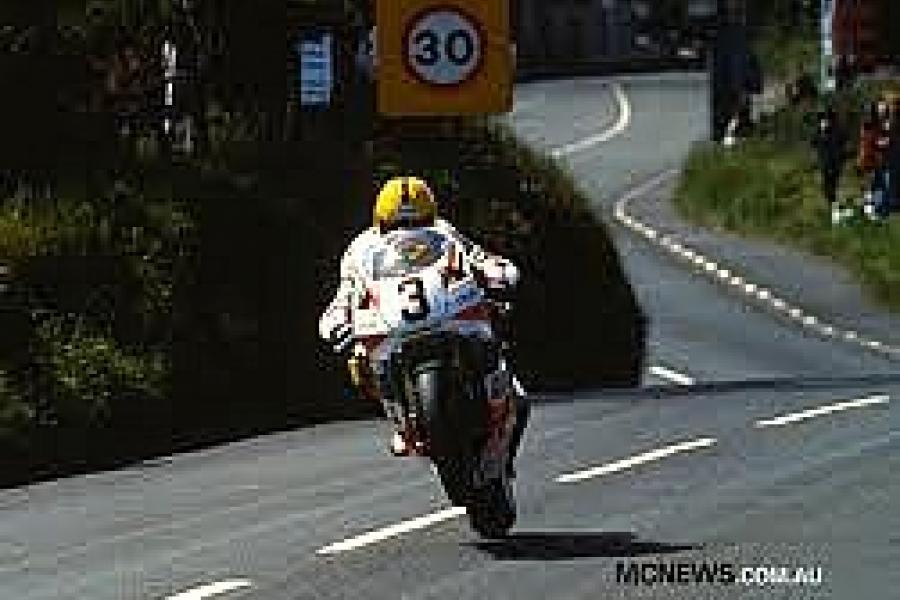

Even today new stories are added like that of the 2010 crash of Conor Cummins. Cummins fell at 130 miles per hour at The Verandah and the story of the crash was retold again and again during our eight day stay. Most of us had seen the helicopter footage of the crash, in our case on the big screen in 3D at the cinema. Most riders, like me, would have had a sick feeling in the base of their stomachs when they saw smoke plume from the back wheel and understood, even before the bike had fallen, that there was no way back and no where to go but over the edge of the mountain. Many would have stopped on the road to examine the site and consider what had happened there. Cummins lived (but only just) and recovered to ride again in 2011; a modern legend of the TT.

A hundred years of these stories mean something to those who keep them alive. They mean something to me at any rate.

The real enigma of the TT, however, lies in the realisation that the TT celebrates the freedom to choose to do risky things. At a time when our own society is increasingly risk averse, the TT celebrates the folly of its dangers. Bike riders understand this intuitively. They know what they do is risky and that is part of its attraction. They calculate the risks and accept them willingly as part of the deal. What they hate are attempts to legislate the risks away. For this reason alone the TT should be preserved and honoured as an antidote to a society that might protect its children from every risk and, in doing so, doom itself to a future of mediocrity. The TT reminds us that you can't win without taking risks and that sometimes just to survive is to be a champion.