Mountains, Canyons and Culture (Originally posted 19 Oct 2015)

Country

This is a short story about mountains, canyons and the resilience of culture and belief. It starts in Creel where we had found shelter from the cold and rain and the services of a couple of bush-mechanics who should be working for Rolls Royce. The business of Creel is tourism. It provides the stepping off place for a thousand adventures in and around the “Copper Canyon” and ensures that visitors are well housed, fed and watered. It is a little rough around the edges but we liked it and, importantly, liked the options it gave us for accommodation and meals. It also has a worthwhile local history museum that is certainly good value for the AUD1.00 entry fee.This is a short story about mountains, canyons and the resilience of culture and belief. It starts in Creel where we had found shelter from the cold and rain and the services of a couple of bush-mechanics who should be working for Rolls Royce. The business of Creel is tourism.

It provides the stepping off place for a thousand adventures in and around the “Copper Canyon” and ensures that visitors are well housed, fed and watered. It is a little rough around the edges but we liked it and, importantly, liked the options it gave us for accommodation and meals. It also has a worthwhile local history museum that is certainly good value for the AUD1.00 entry fee.

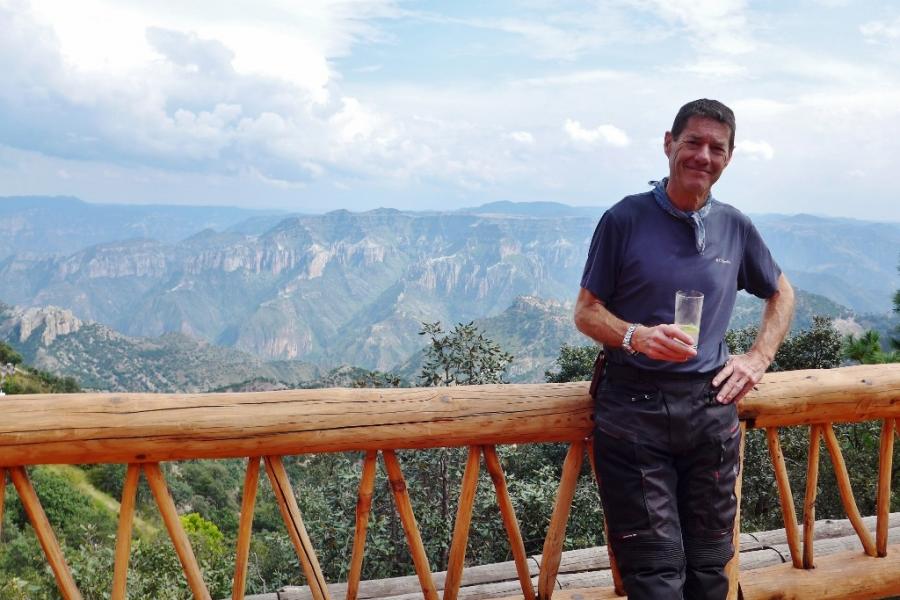

There are six Copper Canyons carved into the limestone and conglomerate of the Sierra Madre Occidental by six separate rivers. Together, the canyons are four times larger than the US Grand Canyon. They do not, however, contain any copper and derived their name from a greenish lichen growing on the rocks which the early Spanish mistook for copper bearing ore. What they do contain is silver and it is this metal that brought the Spanish, small pox and Christianity to the mountains.

The local people, the Tarahumara, still occupy these traditional homelands living in isolated clan groups. Their exact numbers are unknown, but it is estimated that about 70,000 souls remain. Some eke out a living selling handicrafts to the tourists, but we saw many more on foot on the isolated back roads where they live a traditional life of transhumance or subsistence agriculture. They were small, finely boned and sturdy, and also proud and aloof. They looked at us, and probably at all outsiders, as barbarians for they see themselves as God's chosen people given this land as a perfect paradise; a familiar tale perhaps. The scientists, on the other hand, believe they are from Mongolian stock and walked down to Chihuahua after crossing the Bering Strait.

The Spanish dealt with them harshly, appropriating their land, forcing them to relocate to large settlements where they could be indoctrinated with Christianity, obliging observance by force, enslaving the men to work in the silver mines and interfering with the women folk. The Tarahumara revolted, waging an on-and-off civil war for 200 years and despite many defeats it was, in the end, the Spanish who left the High Sierra. They have also survived wars with the Aztecs, French and Americans. The miners and drug cartels have come and gone with apparently little impact. These days the threats come from deforestation and a new wave of mineral exploration.

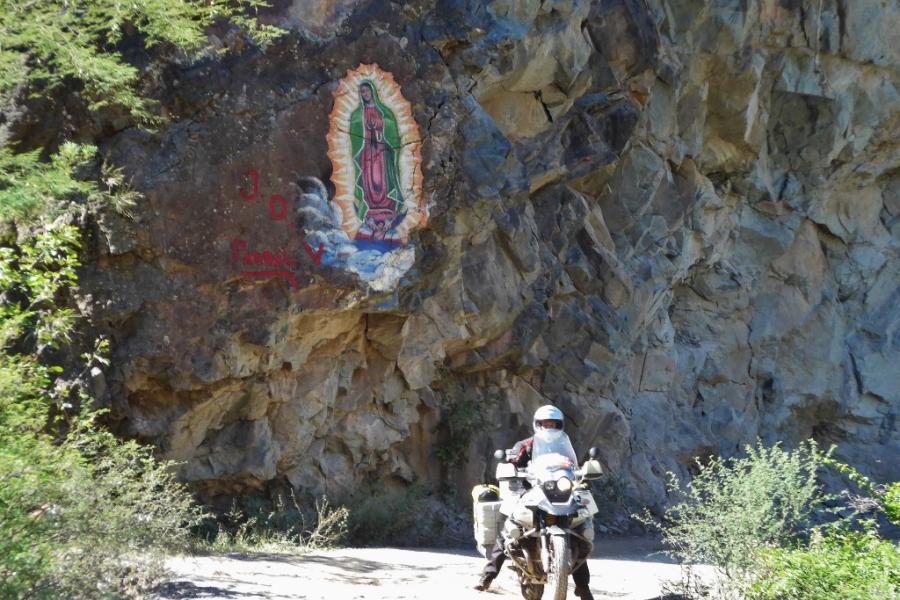

The religion of the Tarahumara is little understood. It is a complex mix of traditional belief and Christian influence. God (who thankfully has a wife) and the Devil are seen as brothers. God created the Tarahumara from pure clay. The Devil created the rest of us from less pure stuff. The Devil, far from being an evil influence, is a protector of life for us lesser souls. Christian observance, originally enforced with the gun, has been adapted around traditional ceremonies, which include the consumption of goodly quantities of corn beer, with the underlying philosophy largely intact. For our part, we decided not to treat the Tarahumara as a tourist attraction and declined to take photos of them in their colourful garb.

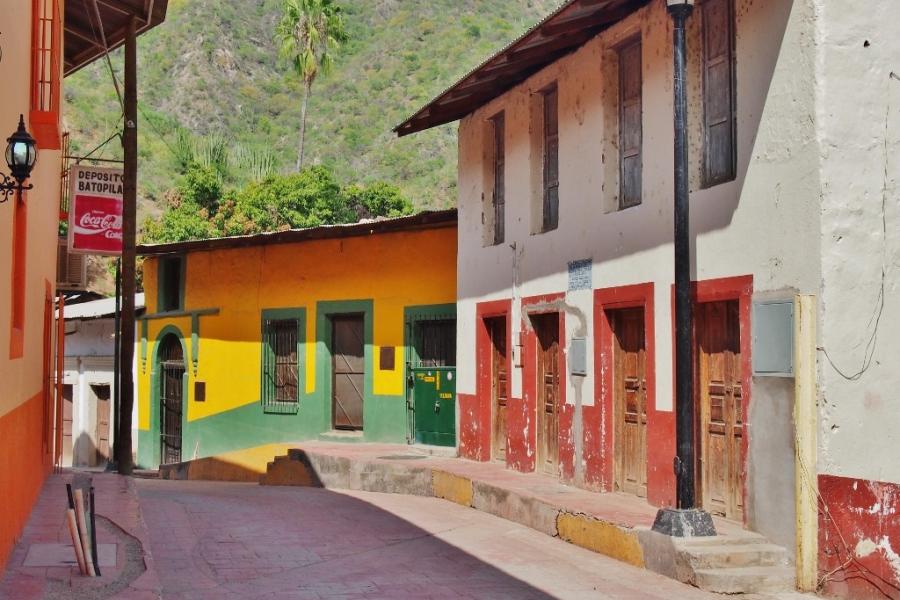

For motorcyclists like us the must-do Copper Canyon adventure is a ride down into the Batopilas Canyon to the old mining town of Batopilas. The road is legendary and, although it has been improved in recent years, the 120km journey down took all day. The road dropped 2000m in less than 30km and, even on recently resurfaced parts, the corners were covered with fine gravel that had the traction of ball bearings. In several places I asked Jo to get off and walk across small bridges with no sides and a long drop to the rocks below, but mostly we just plodded through in our usual steady way.

Batopilas can be a dangerous place if the Federales have been busy burning the local “cash crop” in which case the boyos make up the shortfall by robbing strangers. We were cautious as always, but didn't wander the town after dark and settled back into our little hotel where we had secured Elephant by riding it through the owner's house. The next morning I bought 10 litres of gasoline from a girl who siphoned it from a plastic drum with practised ease, then we started the long haul back up the canyon. When we saw Tarahumara on the road we always waved even though we knew they wouldn't wave back. We did this because that's what we do and because we have never thought that we were chosen for anything in particular and are quite happy to accept that we are lesser souls made of impure clay.

There are six Copper Canyons carved into the limestone and conglomerate of the Sierra Madre Occidental by six separate rivers. Together, the canyons are four times larger than the US Grand Canyon. They do not, however, contain any copper and derived their name from a greenish lichen growing on the rocks which the early Spanish mistook for copper bearing ore. What they do contain is silver and it is this metal that brought the Spanish, small pox and Christianity to the mountains.

The local people, the Tarahumara, still occupy these traditional homelands living in isolated clan groups. Their exact numbers are unknown, but it is estimated that about 70,000 souls remain. Some eke out a living selling handicrafts to the tourists, but we saw many more on foot on the isolated back roads where they live a traditional life of transhumance or subsistence agriculture. They were small, finely boned and sturdy, and also proud and aloof. They looked at us, and probably at all outsiders, as barbarians for they see themselves as God's chosen people given this land as a perfect paradise; a familiar tale perhaps. The scientists, on the other hand, believe they are from Mongolian stock and walked down to Chihuahua after crossing the Bering Strait.

The Spanish dealt with them harshly, appropriating their land, forcing them to relocate to large settlements where they could be indoctrinated with Christianity, obliging observance by force, enslaving the men to work in the silver mines and interfering with the women folk. The Tarahumara revolted, waging an on-and-off civil war for 200 years and despite many defeats it was, in the end, the Spanish who left the High Sierra. They have also survived wars with the Aztecs, French and Americans. The miners and drug cartels have come and gone with apparently little impact. These days the threats come from deforestation and a new wave of mineral exploration.

The religion of the Tarahumara is little understood. It is a complex mix of traditional belief and Christian influence. God (who thankfully has a wife) and the Devil are seen as brothers. God created the Tarahumara from pure clay. The Devil created the rest of us from less pure stuff. The Devil, far from being an evil influence, is a protector of life for us lesser souls. Christian observance, originally enforced with the gun, has been adapted around traditional ceremonies, which include the consumption of goodly quantities of corn beer, with the underlying philosophy largely intact. For our part, we decided not to treat the Tarahumara as a tourist attraction and declined to take photos of them in their colourful garb.

For motorcyclists like us the must-do Copper Canyon adventure is a ride down into the Batopilas Canyon to the old mining town of Batopilas. The road is legendary and, although it has been improved in recent years, the 120km journey down took all day. The road dropped 2000m in less than 30km and, even on recently resurfaced parts, the corners were covered with fine gravel that had the traction of ball bearings. In several places I asked Jo to get off and walk across small bridges with no sides and a long drop to the rocks below, but mostly we just plodded through in our usual steady way.

Batopilas can be a dangerous place if the Federales have been busy burning the local “cash crop” in which case the boyos make up the shortfall by robbing strangers. We were cautious as always, but didn't wander the town after dark and settled back into our little hotel where we had secured Elephant by riding it through the owner's house. The next morning I bought 10 litres of gasoline from a girl who siphoned it from a plastic drum with practised ease, then we started the long haul back up the canyon. When we saw Tarahumara on the road we always waved even though we knew they wouldn't wave back. We did this because that's what we do and because we have never thought that we were chosen for anything in particular and are quite happy to accept that we are lesser souls made of impure clay.