Go and look for yourself (Originally posted 25 Dec 2015)

Country

Another day another border. Costa Rica to Panama was, however, a relaxed affair with just the mandatory confusion caused by poor signage and an illogical layout of offices. In some places they make an extra effort. The easy crossing got us down to the regional city of David (Da-vid) by early afternoon with plenty of time to seek out a good hotel for a longer stay.

As usual, we had planned a route into and through the town to pass by the hotels that might interest us with those of the highest priority first. This little bit of homework can save a lot of misery on a hot day in heavy traffic in a place you don't know. We had our second piece of good luck for the day when the first hotel on our tour, Hotel Alcala, had a room available and was ideally located for our mission in David. The place also had the busiest hotel restaurant we have seen. It was packed with people from breakfast until late and shoveled out huge plates of home cooking (tipico food) to mostly regular customers. This is just the sort of place we like to eat where the turnover is high and the locals tuck-in with gusto.

Our main purpose in David was to get Elephant stored in the Aduana (customs) bond-store located near the David Airport. Unlike the bond-store in Panama City, the one in David had a secure warehouse and considerably cheaper rates. So, with this as our aim we launched into a frenzy of activity. Within a day we had found a car wash and paid $3 for a bath for Elephant, had a haircut ($2), found a laundry and had our stinking riding suits washed ($10), reorganised the luggage to select what would stay on Elephant, found the Aduana and negotiated a storage deal at $1 a day, prepared Elephant for storage then rolled it into the warehouse and said goodbye, had the Customs officer cancel the vehicle stamp in my passport, purchased two cheap suitcases, organised bus travel onwards to Panama City and booked some airline tickets from Panama to Brisbane. All of which seemed like a good day's work.

There was, however, a problem. Elephant was suddenly gone from our lives and we felt naked, vulnerable and leaden. It was as though someone had stolen our pants and left us bare-arsed in the street with millstones around our necks. It is always the motorcycle that frames our journey and it allows us an extraordinary lightness in the way we travel. With Elephant, we simply throw a few bags on and ride off. We change our minds and our destination on a whim. We glide though the world without much friction and, if things get dodgy, we just get going. Suddenly, we were anchored to luggage and timetables and bookings and all that goes with it. It did not feel good.

We manned up and got on the Panama City bus for the eight hour ride to the capital. The modern double decker coach was comfortable enough and had an excellent sound system. Unfortunately this translated into eight hours of over-loud, over-sentimental, over-produced Latin Pop. It was enough to last a lifetime and I found myself wondering: Chrissie Hind, where are you when we need you?

As for Panama City, it was as big, cosmopolitan and as sophisticated as you would like. We managed a couple of days of tourist stuff while we argued with an incompetent (Australian) company about our tickets to Brisbane. The Panama Canal was the first priority as it is the very foundation of the country. Panama was carved off from Colombia by the US with some classic, and literal, gun-boat diplomacy as part of the American purchase of the canal project from its bankrupt French owners.

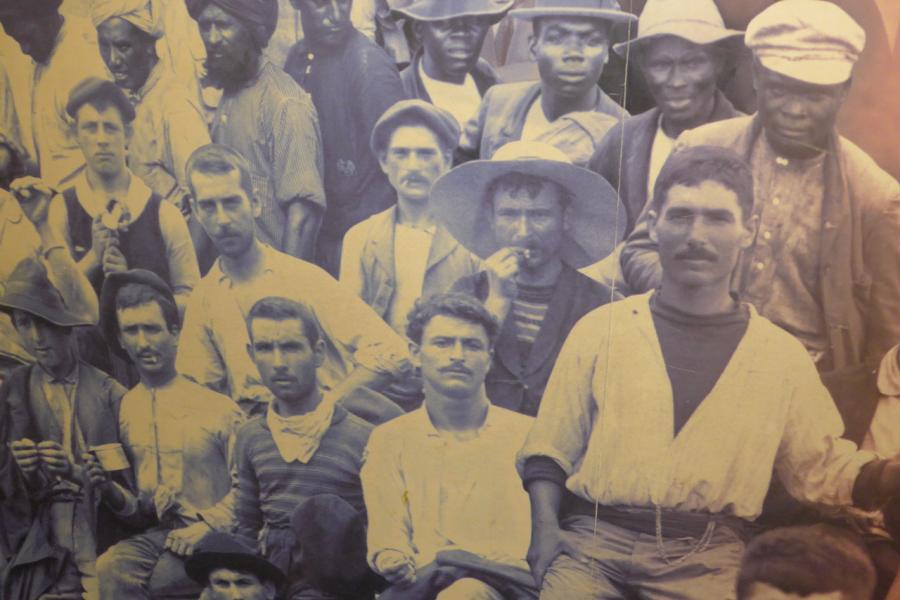

The visitors' centre and museum were crammed with tourists jostling for a vantage point overlooking the Miraflores Locks to see a container ship make the passage. The museum, however, was rather limp. This was unfortunate because the building of the Panama Canal was one of the great dramas of Western Civilization and a testament to French vision and American can-do engineering. I clearly remembered learning about it as a 1950s schoolboy when a romantic view of Western capability was still abroad. It was then, and remains, a great story with wonderful characters. The charismatic Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps who, having successfully built the Suez Canal, put together the original syndicate and raised the funds to begin work. Fourteen years later the French effort collapsed in bankruptcy with tens of thousands of workers dead from yellow fever and malaria.

The intrigues that followed saw the US back a Panamanian independence movement and use its navy to prevent Colombia from reclaiming its territory. In return, the US signed an agreement with the newly independent country of Panama and purchased the remains of the French effort for a song. All of this great drama, however, was just to set the stage for the US construction of the great canal. Led by a US Army Corps of Engineers Colonel, George W. Goethals, the Americans first built a country free of yellow fever and malaria and then built a canal.

This involved ground breaking science to identify the causes of yellow fever and malaria, which became a case study in good scientific method in action. The real heroes of the canal were not the engineers but rather the Sanitation Officer, Colonel William C. Gorgas, and Cuban physician Dr Carlos Finlay. Between these two, yellow fever and malaria were controlled and the lives of thousands saved, Panama City was paved, the water supply was made safe, sewerage systems were built and an extensive mosquito eradication program eventually rid the country of these deadly diseases and allowed the canal to be built in just 10 years. It is a great story, but a story almost entirely missing from this poor museum and, I suspect, from modern Panamanian consciousness. Perhaps this is not surprising for it is, in the end, not their story.

Our other bit of touristic dalliance was a visit to the Biomuseo of Panama which is housed in a spectacular building designed by Frank Gehry. We were told the building had been designed to reflect the Panamanian land and climate but it looked a lot like every other Gehry building we had seen; like it was designed by folding sheets of cardboard. It was certainly a spectacular building but didn't strike Jo (who is sensitive to these things) as a particularly good museum space to house the modest but high quality exhibits.

My coolness for these apparently worthy museums may not, however, be as rational as I make out. We were both suffering more than a little withdrawal after packing Elephant away and this had left us flat and lacking our usual enthusiasm. This always happens at the end of each journey as our attention shifts slowly back to more prosaic matters at home. It also highlights one of the great truths of travel. What you experience on a journey is always highly personal and specific to a time. The Greek Heraclitus summed it up succinctly about 500 BC as follows:

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.”

Our friend Les told us a great story from his own family that illustrates this beautifully and which I will retell as accurately as I can. It seems Les' parents spent about 15 years sailing around the world when Les and his brother were young men. They returned with only a handful of photos from all that time. One night at dinner, a guest asked why there were no more photos because he wanted to see what these exotic places were like. Les' dad answered simply:

“If you want to know what it is like, go and look for yourself.”