Valparaiso (Originally posted 23 Jan 2017)

Country

Some places have names that stir the heart. Often it is a place far away and exotic, sometimes the site of grand legends, sometimes just a few lines of a tale told by a guest and overheard by a boy secretly listening long after being dispatched to bed. Over the years we have run down many of these legendary places and some names now have substance in our memory. Vladivostok took form during a few weeks of summer we spent there refitting Elephant after a trans-Russia ride. Damascus changed from a legendary name to a place we knew intimately where we worked and raised our family for a while. Sometimes these places have been as exotic as we had hoped, more often, however, we have found a gritty commercial town and a barely accessible past. That, or perhaps there still is a “gin joint” remaining in Casablanca and we just somehow failed to find it.

Valparaiso was a name like that for me, a name I carried forward from childhood memory, ill-defined and very exotic. There is probably good reason for this. Valparaiso was a major sea port long before there was a European settlement in Australia. By the time the British had put the fledgling penal colony in New South Wales on a secure footing in 1819, the new nation of Chile was establishing itself as a naval power in the Pacific. From these beginnings, Valparaiso’s importance grew throughout the 19th Century as a victualling port for ships rounding the tip of the continent and for the export of Chilean wheat to feed the American gold rushes. It was certainly well known in the new colonies of Australia.

In 1806, the British came up with a plan which linked the new enterprise in Australia with Valparaiso that was silly even in this time of buccaneers, scoundrels and freebooters. The idea was that a couple of companies of soldiers from the New South Wales Corps and a group of convicts from the Sydney penal settlement would embark for Valparaiso, capture the city and port then link up with British filibusters who would capture Buenos Aires and the Plate River Delta. The plan was abandoned when the sturdy locals of Buenos Aires ejected the British, dashing plans for easy riches and ending the attack on Valparaiso. It is doubtful if the Valparaiso expedition would have done any better than the ill fated one on the River Plate. The New South Wales Corps were jailers not soldiers and, like some others in their position, were more corrupt than the prisoners they supervised. They were most unlikely invaders.

In the year 1834 a group of convicts led by James Porter stole a government brig, the Fredrick, and set sail for Valparaiso. Only Porter had any experience as a seaman but the absconders managed to successfully sail their tiny vessel across the Pacific. They scuttled the Fredrick off the Chilean coast. They then made their way to Valdivia, that Chilean city we visited a week or two ago, in a whaleboat and told the locals they had been ship wrecked. Six of the escapees disappeared, never to be heard of again while four remained in Valdivia, and started a new life. This was, unfortunately for them, a bad mistake. A visiting British man-of-war discovered the four and they were recaptured and returned to New South Wales with extended sentences. Porter did however, prove his resilience by making another escape in 1847, this time successfully.

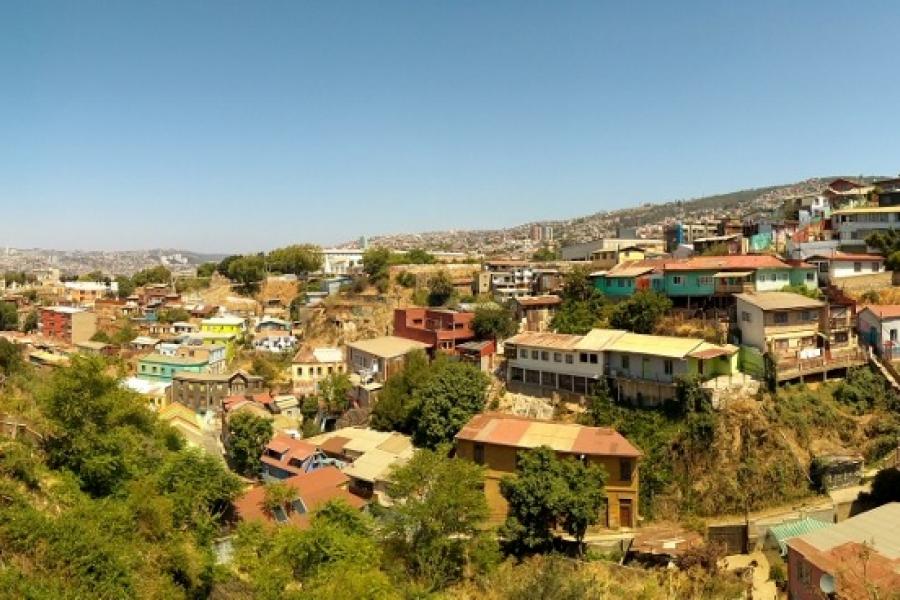

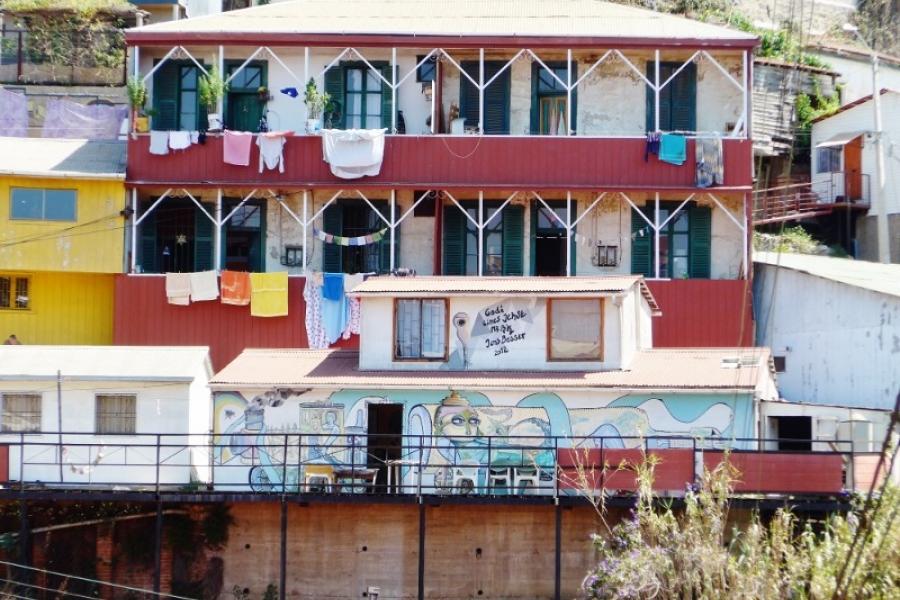

Modern Valparaiso is, of course, a huge city sprawling out to the north in tracts of apartments and shopping malls which are remote from the romantic history of its port. The port too is now a modern container terminal secured behind high fences and almost devoid of people. Despite this, the old town remains in its decrepit glory, clustered around a couple of steep hills and clinging to the rocks by sheer determination alone. For our visit we did the sensible thing and avoided the new city entirely lodging ourselves in an excellent hostal close to the historic centre.

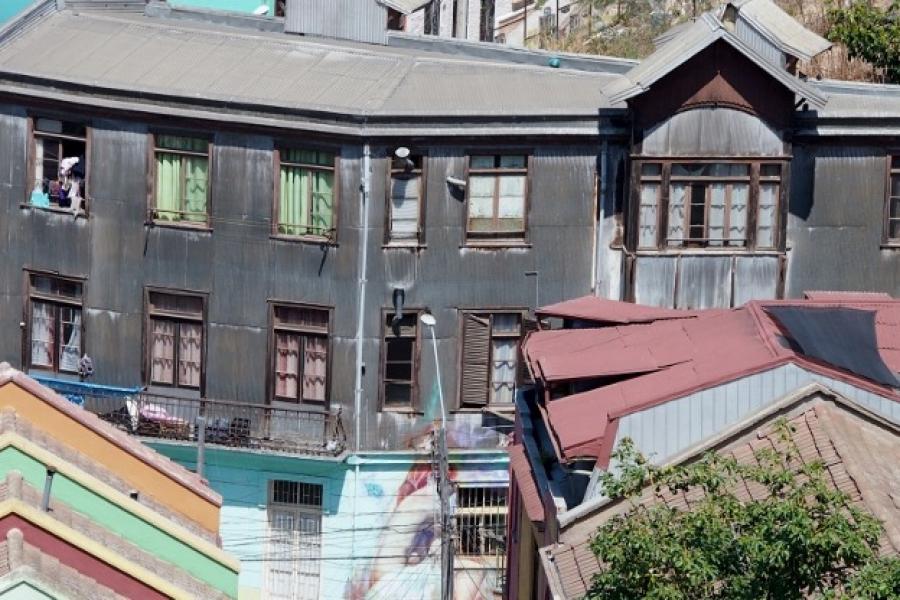

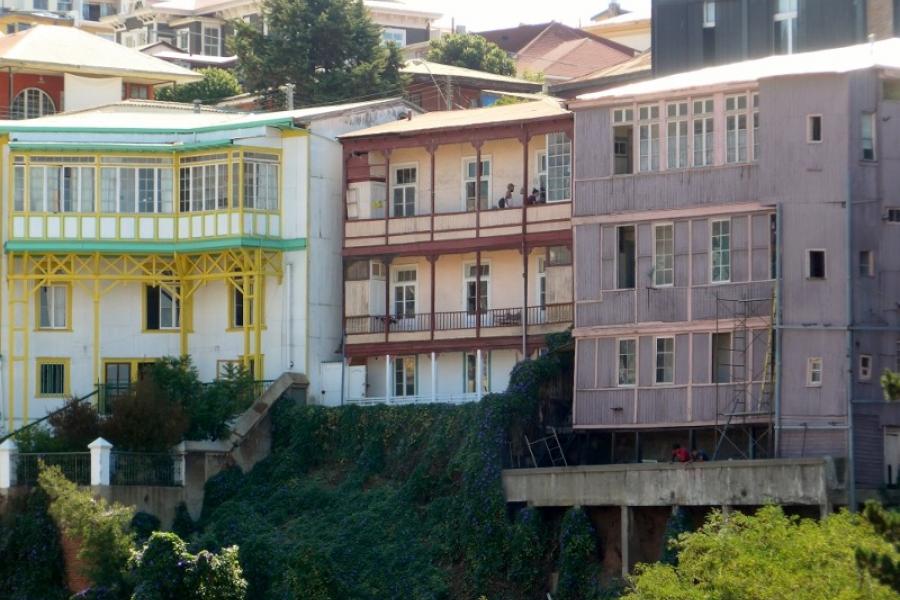

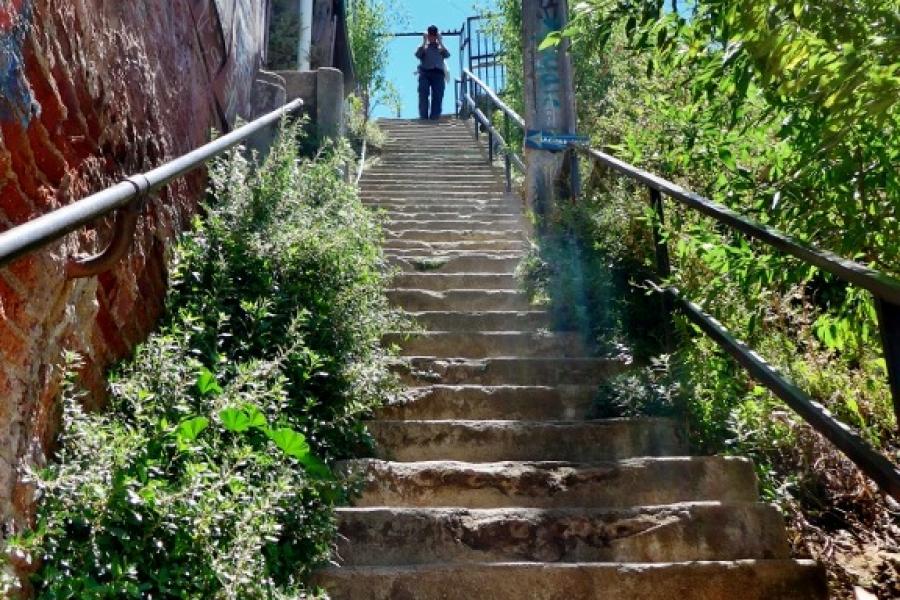

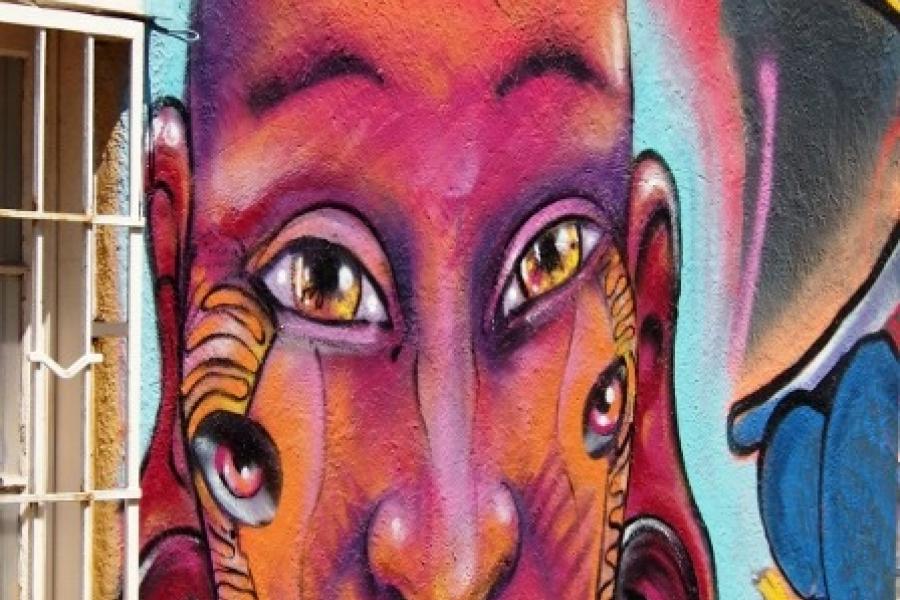

There was much to delight us in this shambolic cluster of timber and corrugated iron. The buildings were light and cheeky, seeming to dare an earthquake to shake them loose from the hills. They disguised their flimsy design and humble materials behind elaborate façades and, wonderfully, bright and inspiring street art. We spent the best part of our week clambering up and down the precipitous steps that link the streets of the old town to discover and photograph murals from the sublime to the spooky.

For me there was another special delight. Old Valparaiso triggered memories of childhood summers spent at my grandparents' house in a old part of Sydney called Balmain. By the mid-1960s the humble wooden houses that clustered on a steep headland had been cleared for concrete and brick apartment blocks, but in those far off days this was an old working class area huddled around the working port. Wooden houses clung to cliff tops and jostled for space. Street kids had adventures along the wharves, fishing for leatherjackets and throwing food to the fairy penguins. There was vacant land too, just like we saw in Valparaiso, where gangs of us kids hid and played and climbed and made friends and enemies and grew up strong and resilient. It was a poor area but, looking back, we considered ourselves fortunate and in hindsight, we were. Nearly 60 years later a sudden glimpse of a gully of scrappy old houses and weedy overgrown vacant land sparked something of the feeling of adventure and excitement of being alive at that place and time. From that point on, I was sold on Valparaiso.

As we finally packed to move on, I was left with the feeling that more had been lost with the clearance of those Sydney inner city slums than was ever gained. At least in Valparaiso the core of the old city has been retained and serves not only as a window into a lost past, but also as an example of how communities can live and work together and build something richer than their humble buildings would suggest. I hope Valparaiso cheats the earthquakes and lives on forever.