The Wandering Equator (Originally posted 24 Oct 2016)

Country

The equator is a big deal in Ecuador. If the name doesn't give it away then the early advice that you must visit Mitad del Mundo (The Middle of the World) does. It may well be the second thing you hear when you come into the country. The first is likely to be the interesting fact that Panama hats are in reality Ecuadorian hats made from Ecuadorian reeds. Many thousands of them were exported to Panama for the workers on the famous canal and hence the association with Panama.

Despite Mitad del Mundo, an equatorial theme park outside Quito, being Ecuador's number one tourist attraction we didn't rush to visit. The Equator is 40,075 km long and it was a little hard to get excited about any one point on its length. Everyday millions of people walk back and forth across it going about their business. It is probable that somewhere, in some country, there is a couple sharing a bed with the meridian running right down the centre with himself in the north and herself in the south. I have no idea if it makes for good sex!

Instead, we drifted down from Colombia, along the Andes cordillera staying at the cool altitudes above 2600m and getting used to a new country. A few days in the capital, Quito, were enough to walk a worthy, if unspectacular, colonial city, made poorer by the work of spray-can taggers, and to ride the Quito Teleferico (cable car) to an altitude of 4050m for a spectacular view of the valley. On our last morning in Quito we decided to loop back to the north to visit the famous monument and make our own cheesy photo straddling the meridian.

Well, Mitad del Mundo is indeed cheesy, but at its core there is a heroic tale and a comedy of errors both of which are worthy of the retelling. The story begins in the 17th Century when two of the great scientific minds were at odds about the shape of the earth. The French philosopher Descartes opined that the world was egg shaped and elongated at the poles. The English scientist Newton took the view the world was spherical but flattened at the poles. This was more than a dispute between great thinkers. An accurate knowledge of the shape of the earth was essential to accurate navigation and a navy that could navigate reliably was essential to building an empire.

In 1735, the French Academy of Sciences supported by King Louis XV decided to settle the issue and launched the French Geodesic Expedition consisting of two surveys, one in Peru and one in Lapland. The aim was to compare the measurement of one degree of latitude along a meridian line and determine the difference. This would allow the accurate measurement of the curvature of the earth. It seems simple when you say it like that but 300 years ago, with the scientific equipment of the time, it was a herculean task. The teams departed in 1736.

All did not, however, go well. Hampered by under-funding, fraud, appalling management and scientific rivalry, the expedition to (what is now) Ecuador did not return until 1744. It is testament to the sheer determination of the French and Spanish scientists who made up

the team that they persevered to prove the curvature of the earth and provide the first accurate measure of the earth's circumference. Their work had far reaching consequences, and not just for the development of accurate navigation (Captain James Cook was the beneficiary of this a few decades later). It also, for example, enabled the development of the Metric System of linear measurement.

The comedy came later, in the 20th Century. In the 1930s a campaign was mounted by Ecuadorian geographer Luis Tufiño to record the important work of the French Geodesic Expedition. By 1939 a modest monument had been established in an area of Pichincha Province just outside Quito. In 1979, the provincial government saw the tourist potential of the monument and started redevelopment of the site and there has been continual redevelopment since. Today, it is a sort of equatorial theme park complete with yellow line to mark the meridian and a full range of tourist shops and diversions. It is also an important money spinner.

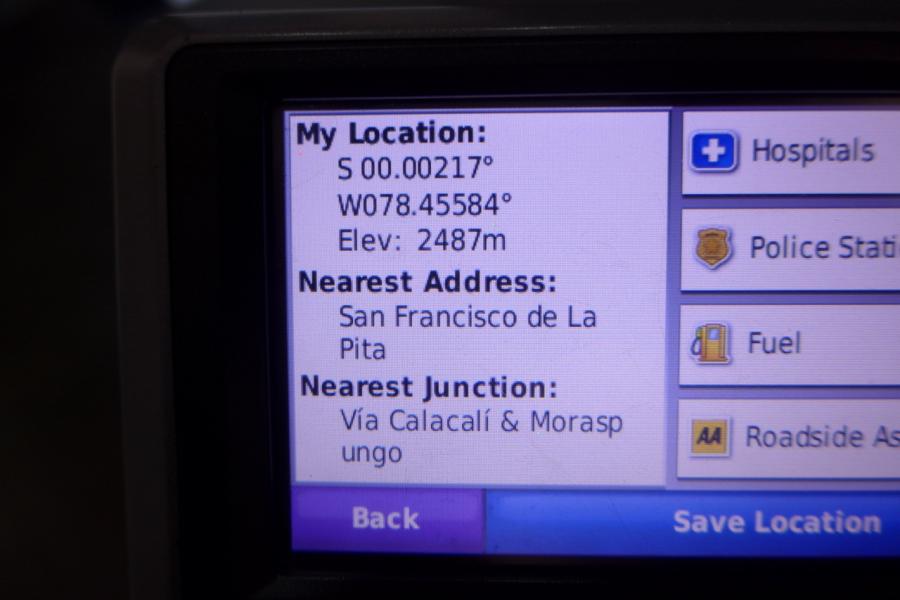

There were, unsurprisingly, two problems. The first is that there is no evidence that the 1736 expedition ever went near Mitad del Mundo. The second is that the monument isn't on the equator. Some enterprising locals got their hands on a military grade GPS and demonstrated what the natives claim to have known all along. The Equator is 240m north of the monument. With admirable enterprise they have set up their own, somewhat less grandiose, exhibit complete with drains emptying in opposite directions. None of this is mentioned at the official site.

All of this was worth a good chuckle as we watched the tourists stand with one leg on either side of the yellow line in front of the towering monument but 240m south of where they thought they were. In the end, however, we decided that it doesn't really matter. Those worthy 18th Century scientists were brave, determined and tough. If it takes a little spacial inaccuracy to ensure their heroism is remembered, then that is OK by us.