Iran: A Storm Brewing

All of the travellers we had met said that Iran was a wonderfully hospitable country, with fabulous culture and sights. It sounded like a hotter version of Turkey, with cheap petrol but with just one social minefield; a strict female dress code. Of course our expectations were wide of the mark again; Iran is much feistier, challenging and tiring than we imagined.

Before crossing the border from Pakistan into the far south of Iran we had to get Georgie into fancy dress. Everyone knows that the country insists that women wear the veil, but what that actually means is not at all clear. We had received mixed messages about the dress code and how much flesh/body shape she could show. We knew that she didnt have to wear a burqa (a full-length black tent with a face grill to look through) the only place we saw that was rural Pakistan. But we were variously told to buy a chador (literally a tent to cover everything except the feet, face and hands), a manteau (a long trench coat), and a hejab (a hood, like a nuns wimple). Others stated that wearing baggy clothes and some form of head covering (a full headscarf) was sufficient. Opinions were also divided on whether she would have to wear socks under her sandals, to prevent men from being driven wild by her sexy ankles!? At the same time we heard stories from travellers who turned up in the country wearing very modest clothes, only to be laughed at by the locals saying we havent worn anything like that for years.

The common theme seemed to be wear baggies and some form of head and neck covering. So to save money, indignity and stupidity (like wearing a trench coat in 44 Celsius weather) we decided to spend as little as possible before hitting Iran; once there wed buy what the local women were wearing. All we had to do was get across the border without being turned back for indecency. To this end we bought a hejab (nuns on the bike run) to go over her head and neck.

One thing we couldnt work out was the logistics of taking off the crash helmet and putting on a head covering without exposing your hair. Our two female biking friends from Belgium (Iris and Trui) pointed out that exposing your hair like that would be like someone taking off a T-shirt showing naked breasts in a shopping mall in, say, Stratford-upon-Avon. Obviously a shocking prospect, apart from on a Friday night where in Stratford (like any English market town), girls getting their breasts out is a common occurrence. So the horrible nylon hejab was worn under the helmet!

So we crossed the border with Georgie wearing my pyjama top (the baggiest thing on earth), baggy hiking trousers and hejab. No complaints and no laughs; only a boil-in-bag Georgie, gently simmering. Our passports were checked 10 times, the carnets 4 times and then out onto good roads as promised. The first police checkpoint showed a marked change from the laid-back approach in Pakistan. All of the police were young lads who brandished their Kalashnikovs skywards, butt on the hip in a much more threatening way than in Pakistan, where people just carried them like a handbag, either in hand or over the shoulder,

Gently simmering - Florence of Arabia

Into Zahedan, which set the scene for most other Iranian cities. The roads were full of Paykan cars; exact copies of the British Hillman Hunter from the 1970s. They were boxy and crap then, and theyre boxy and crap now, but it did give the Iranian roads a strange time-warp effect. Many Paykans are shared taxis, which pull over at the drop of a hat and cause traffic chaos. And most roads in Iran share a common set of names how many Emam Kohmeini Streets did we to go down during our visit?

Back to the future in a Paykan taxi

Six hours into the country and Georgie was already pissed off with the dress code. We had heard that is was not acceptable for women to walk around their hotel corridors without the proper dress. So every time she wanted to go out and use the shared toilets (cheap hotel) she had to get dressed up again. What a faff!? She got really tearful and depressed and we started to consider getting out of Iran ASAP. But we decided to give it a few more days and buy some cooler cotton clothes. If after that time Iran was not so special, wed shoot off to wonderful Turkey and go on holiday there.

Next morning we discovered that the BMW had been tampered with overnight. The comical Dog Horn that Id bought in India (it sounded like a clowns klaxon) had been stolen, one pannier had been forced and the petrol stove taken; all in a supposedly safe, locked area of the bazaar. Wed need to be more careful in Iran. Then I was off to the bank, as Georgie was disinclined to go out in the veil. Whilst faffing around for an hour I worked out how the Iranian financial system works. There are no credit cards so people who want to send money through the post have to buy promissory notes from the bank; just like old-style Postal Orders in Britain. I bet you could buy a 1970s Hillman Hunter copy with 1970s style postal orders.

Then off towards Bam after filling up with that lovely cheap petrol, which turned out to be a really difficult thing to do. REALLY!! We eventually found a petrol station at the back of a truck stop, and there was a 100-car queue waiting for fuel. And you had to pay for the fuel before filling up - just like in Russia. Luckily we skipped the queue and I eventually got the hang of how much to pay. But why the queue for heavens sake? There cant be a petrol shortage in Iran!

Queuing for petrol

Well there is no shortage of petrol, but there is a shortage of petrol stations. With petrol being 8 cents (about 5p) per litre, there is no profit to be made from selling petrol, so nobody opens petrol stations. Perfect logic. And to exacerbate the situation in Zahedan, there is a problem with petrol smuggling. People buy petrol in Iran and take it over to Pakistan and sell it for a huge profit. So the petrol station we visited has to record the registration number and fuel usage of everyone who buys petrol, to make sure theyre not smugglers.

And the problem with paying for the petrol? A curious Iranian custom in pricing caught me out. The currency is Rials, but most retailers usually quote prices in Tolman. A Tolman is equal to 10 Rials. So when a petrol pump man writes down 2600, he could be asking for 2600 Rials or 26000 Rials. Its easy once you know how much things actually cost, but a pain to learn. We were to spend a couple of weeks trying to work out where this silliness originated. We discovered that there never was an official unit of currency called a Tolman, and the reason for using the Tolman was to cut down the number of zeros in prices. But causing all that confusion just to get rid of one 0! Its like saying that a £6,000 bike is 600 £10s; daft! And reading the Lonely Planet guidebook, it seems that some market traders use Tolmans that are 100 Rials or 1,000 Rials. As clear as mud!

Onto the highway and 320kms across desert mountains and then a long pull through our hottest desert plain yet. We got the thermometers up to 52 degrees in the shade thats 126 Fahrenheit! And Georgie was still wearing that damned nylon headscarf under her helmet. Not surprisingly at one point she keeled over and the scarf came off for good.

At a lunch stop, Carsten and Katrina, a German couple on XT600s who wed met on the KKH, caught us up. I'd left an old back tyre for them in the guesthouse in Quetta, and when we met up again it was mounted on one of the XTs.

The roads were fast and smooth but we only rode at 65 to 75kph, so as not to stress the Enfields engine. Loads of trucks and pickups overtook us, a pretty safe thing for them to do as the visibility ahead was generally about 15kms. For a country that officially hates the USA, there are many American products in Iran. Many of the trucks have long wheelbase, long bonnet MACK tractor units. There are numerous Chevvy and Ford pick-up trucks whizzing around and fire hydrants are copies of US stick up from the sidewalk models. Dollars are easily changed, and most people dine out on burgers and pizzas.

The food in Iran was one of the biggest disappointments. Along with the weird burgers and rubbery pizzas, the standard offerings were sausage sandwiches, tough kebabs and baguettes filled with veggie stuffing. Almost like being back in Manchester! We were delighted to find that ice cream parlours are popular, but crushed when we found that the ice creams are all heavily flavoured with rose water, making even the chocolate coloured ices synthetically perfumed. On the up side though, there is always a plentiful supply of black or mint tea, and the fruit was superb, especially the grapes and plums. When we arrived in Bam we discovered that it is famous for its dates; the place is full of date palms with red dates ripening. But they were not in season and the dried dates were so sweet that you could only eat one before needing a gallon of tea to wash it down.

The other attraction of Bam is the old town and citadel (fort). The place is hundreds of years old and only made from unbaked adobe (mud and straw). This says a lot about the climate! Its an amazing sight, but we were surprisingly unamazed. And we had the same feeling when we visited other sites in Iran. JADED! We had been out on the road for too long, losing the will to see the 10 million and tenth amazing thing, and lacking the energy to deal with and enjoy interactions with challenging locals. I was tired of trying to work places out, just getting one place sussed before moving onto another, even more confounding place: I wanted to live a simple, obvious life for a while. We both knew that it was time to go home, so our itinerary in Iran got butchered, bypassing places of minor interest, leaving only the juiciest morsels to tempt our spoilt palates.

Bam citadel - everything built from mud and straw

After a few days in Iran we were getting the hang of the womens dress code. In traditional towns they wear the chador, basically a black sheet draped over the head and held tight at the front: it covers everything and looks swelteringly hot. Chadors seem to be designed without fastenings, so wearers have to hold the front together with their hands or teeth dooh! Younger traditional women wear baggy trouser suits with a hejab; they look so much like nuns that when we got back to Italy I thought I saw an Iranian woman get off a bus, before realising that the woman REALLY WAS a nun. In modern towns the more rebellious girls push the rules and dress like 1950s cleaning ladies a light overcoat and a headscarf, pushed as far back on the head as they dare. Often they show enough hair to allow a pair of designer sunglasses to be perched on their head. Id regularly see women in cafes walking around with their scarf and coat on, as though theyre just off out for a cold autumnal walk down to the shops.

Wall to wall static cling

Armed with this information we went shopping for an Iranian outfit in the bazaars, only to have another 1970s retro-experience. All of the clothes we found were horribly synthetic made from nylon or acrylic; not a stitch of cool cotton anywhere. So having realised that the dress code was not enforced with a rod of iron, Georgie rebelled and took to wearing her shalwar kameez and scarf. The nylon hejab was discarded (actually it was kept for fancy dress at home) and rather than wearing a scarf in a Mrs Mop meets Jackie Kennedy way (hot and restrictive) she took to wearing it like a Bedouin turban. This is tied to give a tail that can be pulled around the neck and shoulders in public, but can be left to dangle at other times. Although we got looked at lots (as do all foreigners, especially big bald ones), there seemed to be no problem; the police never batted an eyelid and various people complemented her for brightening the place up. The issue of taking the helmet of and putting a scarf on without exposing her hair also turned out to be a non-issue. She just took off her helmet and put a sunhat on pretty sharpish and nobody minded.

What she got away with wearing

Next a three-hour run to Kerman and gradually the BMW starts to feel even rougher than usual. I had problems keeping up with Georgies Enfield up the hills and couldnt even manage 90kph down hills. But as usual the BMW was still running, so the problem could wait until we arrived in town.

The happy hookah

Into a very mixed bazaar the usual dreadful clothes, some wonderfully huge cooking pots, beggars whod square up for a fight if you refused them, and a visit to our first busy teahouse. The function of Iranian teahouses is similar to that of cafes in France and pubs in Ireland; theyre a place to relax and socialise. Like Irish pubs, there are some really beautiful traditional buildings (which attract the well-to-do and tourists) and plain, utilitarian places where working men go to meet. All share three common themes: Tea, smoking and conversation. Tea, black or mint, is drunk sweetened from small bulbous glasses. Skilled Iranian tea drinkers dont put the sugar lumps (chipped from huge sugar loaves) in the tea; they hold a lump behind their lips and drink the tea through the sugar. I can feel my teeth dissolving as I write! Smoking involves water-pipes, the smoke from fruit flavoured tobacco drawn through water so that even non-smokers like us could enjoy the experience. You barely taste the fruit flavour as you inhale, instead you get a burst of perfume as you exhale; mulberry flavour was in season during our visit very pleasant.

Tea, chat and smoke

And then to our first up-market Iranian restaurant and thankfully it is possible to get decent food in Iran; you just cant get decent street food. The olives (finally) and spiced aubergines were outstanding along with a lamb stew called abghust or dizi. This gets cooked and served in a small clay pot. You strain the gravy off to slurp with bread, and then pound the meat to a paste and eat that with rice. Hurrah, we found a way to eat Iranian bread, which is disgusting, unleavened and sold folded like a newspaper. Bread is a fairly new introduction to Iran somebody needs to sell them a giant pack of yeast (maybe disguised as a brewing industry?).

Next day a turn around the citys 800 year old mosque (which somebody has restored to look like a 1960s comprehensive school in England) before bumping into a couple of German overlanders (Kai and Ulrike) and then getting to grips with the sickly BMW. The bike was showing the classic symptoms of perforated carburetor diaphragms; running rough, no power but idles OK. And I was showing the classic avoidance behaviour of not being able to remove the diaphragm chamber top from one of the carbs; cleaning the fuel lines, checking the spark plugs, changing the ignition unit. Eventually I bit the bullet and got into the one accessible carburetor and found that indeed the rubber diaphragm was perforated. No problem as I have a spares..... bugger!....wrong size. I had carried these spares for over a year and they were the wrong ones! There was no chance of buying any locally (especially as it was Friday) so a choice of bodges came to mind. Maybe a repair with a puncture patch, or perhaps fabricate one from a condom. Finally I settled on sticking the holes over with brown parcel tape, which actually held well enough until we got to a BMW dealer in Milan 6 weeks later. Three months later (back in the UK) I eventually got the top of the other carb and found that the diaphragm in that one was perforated as well bloody unstoppable these Beemers!

Dinner with the Germans was useful for all of us. They sucked us dry of information about which roads to use in Pakistan and road safety in India (!) and in return they confirmed that we were not being unduly cranky in thinking that the Iranians were a bit on the feisty side. They also confirmed that Turkey and the Turkish are a lot easier to get on with. I sighed with relief, glad that my observations had not just been intolerance and fatigue. In all of the previous Islamic communities we had felt safe and respected, people acknowledging us with a smile, a nod and assalam alaikum. But in Iran we would be stared at and then assailed with a hello... hello mister... hello and various laughs from behind, and when you turned to see who was shouting, nobody would acknowledge. It was like being a pretty girl walking past a building site; shouts and catcalls and it SUCKED. The problem was reduced in bigger towns (further north) where a few more tourists visit, but we were never really comfortable in Iran.

Three more cities to do on our cut-down itinerary; a few days in Shiraz first. Yes, Shiraz is where the variety of grape originated and yes, mentioning the name did make our mouths water for a glass of wine, but a glass of beer would have been more welcome.

In Shiraz we started to interact with Iranians who wanted to practice their English. Two female students chatted to us. The one I spoke to was amazed that 'they' let Georgie ride her own bike, and I said that 'they' would find it difficult to stop her. When I asked about the overcoat and hejab she seemed genuinely at ease with it, saying that Iran is a hot place whether you're wearing it or not. As we sat in the gardens at the Hafez mausoleum a spirited 18 year old girl came to tell us that Iran is the best place in the world and talked about the wonders of Hafez; Irans favourite poet. She was so boisterous that when she asked the usual question about our religion, I gave her a full blast of atheism and big bang theory. Why are all Europeans atheists? she complained, reminding me of argumentative teenagers in the UK.

Other chance meetings highlighted the political tensions between the supporters and opponents of the countrys religious leaders. Luckily this gave us time to read up about the issues, we were to need the knowledge later....

A major reason for visiting Shiraz is its proximity to Perspolis, the ruins of a 2,500 year old palace complex. It was hidden in the hills until Alexander the Great came along 2,300 years ago and trashed it. Historians cant decide on whether he deliberately destroyed the place in retaliation for the destruction of Athens, or whether he burnt it down during a drunken party! I prefer the Rock and Roll theory; makes trashing your hotel room look a little low budget. The bits of architecture and statuary they have dug up managed to impress us. We were equally impressed with a couple of overlanders we met there. Francesca and Alessandro from Milano were on their honeymoon, riding a BMW F650 to India, intent on using money given to them as wedding presents to build a school for underprivileged kids!

One city down, two to go. The long ride to Esfahan was surprisingly cathartic. We were heading north-west directly home. I dialled Go to Home into the GPS and it told me that at our speed (75kph) it would take 74 hours to get home. Thats just 3 days!!! Unfortunately the GPS was assuming all sorts of silly things, like our ability to ride for 74 hours without a stop, the various towns, borders and seas in the way, and the fact that theres no straight road from Shiraz to Manchester. Whatever, it did make us feel that finally we were getting somewhere.

More immediately though, we now found ourselves heading away from the sun; bliss. Overlanding raises some curious problems, one of which is discomfort from the sun. If youre a lazy soul like Georgie and me, you start riding sometime after 10am. This is OK if youre travelling east, because when the sun really starts blasting in the afternoon, it is on your back. In fact it nicely illuminates things from behind you and the only downside is that drivers coming towards you are blinded, so you have to be more careful. But when you come home (as we had been doing for the past 3 months) the afternoon sun is always in your eyes, and your face is constantly scorched. I now understand why Clint Eastwood had screwed up eyes in the Spaghetti Westerns; it was all that riding off into the sunset. Of course the way to avoid the problem is either to keep going east, or when youre going west get up earlier and get your riding done in the morning. Neither of these suited us and so our turn towards the north was most welcome.

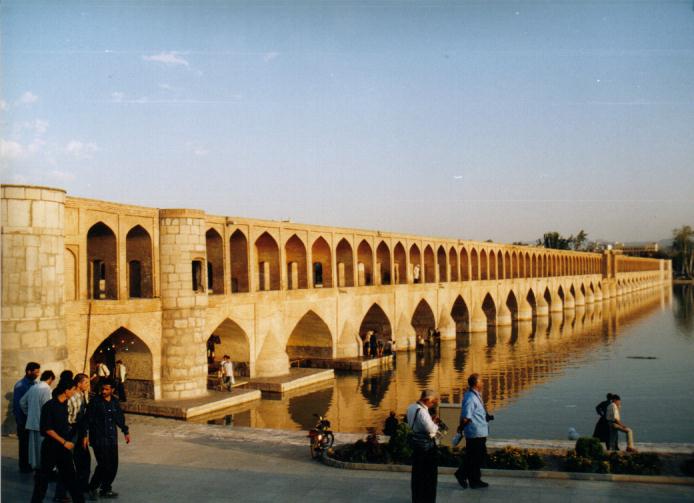

To me the name Esfahan sounds exotic, but it turned out to be the most normal place we had been for ages and had us feeling much more positive about Iran. It was all so modern, with real shops and more western attitudes. We had fewer walk by hellos and more informed friendliness. People were calm and helpful rather than acting like overexcited kids. But still the driving was anarchistic. To add to the general buzz, we arrived at the weekend and the place was full of Iranian tourists, keen to visit the mosques and madressas, which we also enjoyed even though we were mosqued-out. For us the highlight was the riverfront where everyone goes to promenade in the evening; wonderful after six weeks in the desert since our last real river in Pakistan.

The waterfront in Esfahan

More than a week into our visit to Iran I was getting on top of my Iranian faux pas. Its not mentioned in the guidebook, but this one is of Monty Pythonesque stupidity. In Iran, if you give someone the thumbs up sign, it has the same meaning as giving giving someone the finger Europe or the USA, the same as sticking 2 fingers up at someone in Britain. Just think about it for a moment, Im a British biker communicating with all sorts of people on the street, finding my way, finding food, buying petrol. I speak no Farsi, so all communications are done in sign language. At the end of a conversation when someone has gone out of their way to be helpful, I say thanks mate and give him the thumbs up. And surprisingly his face falls or he looks really annoyed; and why shouldnt he because I have just told him to F*** off. And the thumbs up is so ingrained in my habits, I cant help doing it. Petrol pump attendant, thumbs up; hotel foyer bloke, thumbs up; little old lady selling food, thumbs up. Aarrgh; its no wonder theyre aggressive to foreigners, we keep giving them the thumbs up!!

And so onto our final city of Tabriz, breezily by-passing the legendary traffic chaos and superb museums of Tehran. Well take in Tehran another time, when were not driving and when we can face another museum.

The desert highway turned to motorway at Qazvin, and the motorway had lots of signs saying that motorbikes are forbidden, but there seemed to be lots of locals on it so what the hell. We were a little worried when we got to the end of the motorway and came to a toll booth manned by 2 blokes and a policeman. They were just interested in where we were from; in retrospect I think we might be the only people to have used that last kilometer of motorway, as all Iranians turn of the motorway and head across the dirt roads to avoid the toll.

More greenery as we headed north, adding colour to the open plains and distant mountains that wed seen for the past two weeks.

Then it was the turn of Georgies bike to get sick. First it wouldnt start very easily, but I put that down to her being so tired that she couldnt kick the engine over fast enough; I could usually get the bike going first kick. And then it would cough and splutter a bit out on the road. But the problem wasnt bad enough to stop out on the road if its not broken, dont fix it.

The crazy Iranian driving was increasing noticeably as we entered the Kurdish area of the country. One guy in a pickup undertook me and then, smirking broadly, pushed me out into the middle of the road. I booted the back of his pick up, but he didnt hear it so I accelerated and kicked his drivers door. The next 10kms turned into a battle royal as the van driver tried to make me stop so that he could beat me up. Eventually we got into a town were the road was too wide to cut me off; the tussle ended with him throwing his water container out at me across the road. We hightailed and hid in a car repair yard for 10 minutes to make sure he wasn't following us. After that, of course, we saw nothing but blue pickups in our mirrors!

We wondered if we would ever get to Tabriz when a freak windstorm covered the polished tarmac road with a layer of dust from a disused cement factory, and then a cloudburst turned the road into an ice-rink; the dust, old oil and rain forming a soapy froth. I was terrified and carefully pulled Georgie over to ride on the hard shoulder where the tarmac was unpolished.

We looked forward to the old bazaar in Tabriz, kilometers of alleyways and hundreds of courtyards that used to be caravansari. Instead Tabriz was a highlight because of the weird interaction we had with the locals.

As often happened on this trip, things got weird when one of us was out on their own. I left Georgie sleeping off the effects of 940kms over the previous two days and went to an internet cafe where I tried to coax my brother to get some insurance for our bikes and told the rest of the family that we were still alive. A very lively, young local guy came in and after a few moments chatting with the cafe owner, came over and introduced himself as an English teacher... what do I think of Iran and Iranians... what do I think about Orwells book Animal Farm... would I like to come to talk to his class that evening... A million questions in rapid order, his English was good, but so fast that I lost 2/3rds of the words. I accepted the invite, aware that wed not spent enough time with locals. He then went onto more politicised questions about the Iranian Government, whether I thought that it would be replaced soon, did I think that Iranians would be willing to die defending their country... Phew, not lightweight chitchat, especially in a cafe full of unknown people, any of whom could have been secret police. Before he left I told him that wed come to the class, but we wouldn't welcome political chat, as we didn't want to end up in an Iranian gaol!

Evening came and the teacher (Im not giving his name for reasons that will become even more obvious) came to pick us up at the hotel. Its his first meeting with Georgie, so does he ask the usual how are you? hows the trip? type questions; no, straight into what do you think about the situation for women in Iran and how can Iranian women improve themselves. She was shocked, dumbfounded and a little concerned. A taxi to the suburbs and up to a set of small class-rooms on 2nd floor of an anonymous building. Gradually the students arrived: a PhD computing student, 18 year old twins into technical subjects, a 16 year old technology student and a 43 year old engineer who was also a 4th Dan in Karate!

The meeting turned out to be a real Loius Therouxs Weird Weekend experience. Yes the lesson was about learning English, but the main topic for discussion were political dissent! We asked everyone to introduce themselves; the conversation turned to politics. They asked us questions, all about politics. The teacher would interject with quotes from Animal Farm and explain how it compared to Ayatollah Kohmeinis speeches before the revolution. The teacher was hugely excited and talked so fast that we couldnt understand it, let alone the students. The thrust of the conversation was we hate the current regime; what can we do about overthrowing it? There we were sat in a non-secure environment, talking about revolution with a bunch of Iranian students!! We expected masked policemen to burst in at any moment and drag us off. One of the students had already noticed that I share a surname with John McCarthy, a journalist who had been held hostage for 3 years in Beirut! It was so scary that it was funny!

After a while I got a bit heated and asked if they always talked in such way. They all agreed that political discussions were the usual fare! The whole atmosphere was revolutionary. I told them that it reminded me of the radical talk in Russia during the early 1900s, amongst students in 1960s France and in British trade union meetings in the 1970s. And the groups feelings reflected those of the people we met in the street. They ALL asked the same question:

"What do you think of Iranian people?"

To which Id diplomatically reply Iranians seem to be very lively and emotional.

"Yes theyd say the Iranian people are good, only the Government is bad."

As the meeting calmed down we were asked about Britain, but with a political edge.

Why was David Kelly murdered? which was news to us as wed heard that hed committed suicide. We explained about the political processes we knew about behind the decision to go to war with Iraq.

What can you tell us about Bobby Sands? Bobby Sands!!!; now theres a name from the mists of time. He was an IRA terrorist who starved to death during a hunger strike in 1981, and these Iranians wanted to know the full story, right back to William of Orange. What a wake up call for us! Luckily we could make analogies to various Muslim factions fighting each other.

The meeting broke up, but no end to the hospitality. The schools secretary wanted to be hospitable and practice her English a little, so it was back to her flat for beans and meat while we watched illegal satellite. Is there anything more surreal than watching the Jeremy Clarksons Top Gear while sitting on the floor eating stew and talking Iranian politics.

Next evening we were invited out again, this time to a posh restaurant in Elgoli Park.

The park was swarming with locals enjoying the night air, and was still busy as hell when we left at 12.30! Our arrival at 9pm was too early to eat so we sat outside on the terrace and drank tea. PhD man was there with his wife and 16 month child (born about the same time we set off from England and now walking and talking!). A journalist friend had joined us, just back from covering the Gulf war. His line of questioning was even more political than the others, starting with questions about Britains support for the ruling Iranian clerics.

After half an hour of trying to unravel the difference between Iranian conservatives and the British Conservative Party, I got a bit fed up and had a go at the whole group for assuming that we were at all interested in political discussions. They were amazed but understanding when I told them about the British saying that you should never discuss religion or politics with friends. Again amazement that someone from a place where politics vaguely works can be disinterested, but I pointed out that the stability is the reason why normal people don't have to bother with it.

The questions still kept coming. Will the US and UK come in and do a regime change in Iran like they did in Iraq? The rest of the group realised that the political questions were getting to us and spent the rest of the night keeping the journalist under wraps. But not before I spent twenty minutes winding him up with my false Journalists ID Card that I bought in Bangkok.

Next day the run up to the Turkish border. Georgie's bike was now running rough when hot, and she was getting slower and slower; like down to 60kph. So we stopped to clean the carburetor. No effect on the burbling. So it must be the ignition; changed the condenser and points with instant results. Thank heavens for the spares we bought in India.

A full tank of cheap fuel, through the confused Iranian procedures and waited to get the gate to Turkey open. A final conversation with the border guard, practicing his English; the usual things; where are you from, where have you been, do you have children? No children sir, do you have a problem?

The only problem I have is that you wont open that bleeding gate!

The gate opened, press the starter button; click, nothing; click nothing. The starter motor had failed again. So I pushed the bike over a second border, the previous being between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan a year ago.

Two glasses of Efes beer beckoned us from Turkey.

-----------------------

Number of weeks = 2.5

Miles in country = 1,800

Kilometres in country = 2,880

Total miles so far = 29,677

Total kilometres so far = 47,483

-----------------------