Executive Summary

Country

There are things motorcycle travelers want to know about a journey that I did not sprinkle into this journal. I should have kept better notes but I will try to fill in some details.

The bike is a 1996 Honda TransAlp 600, registered in the EU (Lithuania). I had access to it through a relative with whom I did a bike exchange (he rode one of my KLRs to Prudhoe Bay a couple of years ago). The only farkles were Honda hard bags, a Givi top box, heated grips, an SAE plug and cigarette lighter for charging stuff, and a really nice aluminum phone holder that worked like a vice and never let me down.

I found the TransAlp to be an excellent “multi-surface” adventure bike although it is a far cry from an enduro. Perhaps a bit heavy, but nice suspension and enough power for what I was doing. The motor is a flawlessly smooth V-twin with dual carburetors. I have no idea how economical it is to run as the speedo gear went south just as I was leaving Kaunas. The horn is worthless, but in northern Europe I never heard anyone using their horns. The bike has a fairly low seat height, good for old guys, but sufficient ground clearance for travel in most parts of the world. I ran a Mitas tire in the rear and a Dunlop in the front, both about a 70-30 dirt/road tread. I was careful in all the rain I encountered since the tires have no siping. Wear was excellent with probably 50% left on my return. By GoogleMaps, I estimated I covered about 6,000 miles or 9,720 km, which is quite good longevity.

I used a 20-year old Aerostitch Darien jacket with a Kinetsu heated liner, but I only plugged it in the day I made the run to Nordkap and back. The Darien has a frustrating configuration where you can’t unzip the side pockets without a bizarre contortion. Same with the pit vents. Not sure what Andy Goldfein was thinking when he designed this. It also has two Napoleon pockets that are perfect for stuffing gloves into— and for losing cellphones, wallets, toll tickets and other items that you will end up REALLY needing soon. I wore Roadcrafter armored riding pants over quick-drying lightweight “travel pants.” These don’t have very useful pockets either, but they are the pants I have. Despite the GoreTex lining in these garments, I typically end up with a puddle in my crotch, so I also use a 2-piece rainsuit. This also makes a great windbreaker when I don’t want to dig out warmer layers. I brought along heavy-weight gloves with rain mittens as well as my summer gauntlet leather gloves. However, my go-to almost every day was the only “for this trip” purchase I had made: a pair of Held Goretex waterproof gloves that I found on the web for half-price. Impervious, quick-drying, and the lining doesn’t pull out with your fingers like some other membrane gloves do. Goretex Sidi boots were a previous trip purchase and were, as usual, perfect. Grant Johnson told me dry and warm hands and feet make for a happy rider.

Having once travelled for a year with just a single change of clothes in my kit, I now take an extra teeshirt to sleep in and three pairs of sox, all thin merino wool. Everything else comes under the heading of “layers.” I have a thin long-sleeve base-layer shirt, a long-john set, and a two balaclavas, one silky and one flannel. I pack a lightweight pair of cargo pants that I try to keep clean for special occasions and a light-weight long-sleeve shirt. I use my motorcycle jacket liner as a fleece. This set-up has worked for me in Latin America, Alaska, northern Canada, and now in Lapland. It seems to cover warm/cold/wet/dry— whatever comes up.

I took along a backpacking stove that is about the size of a dinner roll but unfortunately it uses gas canisters that take up room. These, however, are readily available all over Europe. My gear included a backpacking cook kit, a very cool Primus-branded plastic plate-strainer-spatula-stirring spoon set-up that was about an inch thick and purchased from Sierra Trading, a discounter. A serrated knife was handy for slicing bread and a small cheese grater completed the equipment. I carried some 35 mm film cans of spices and a few staples like rice, couscous, oatmeal, raisins, a tube of tomato paste, bouillon cubes, and some dried diced vegetable bits to liven things up. Most Scandinavian convenience stores are like small supermarkets and are often stocked with salad-makings, fresh items, and the only bargain in Norway, fresh fish. I had a flask of olive oil and a flask of Jaegermeister for my evening cocktail.

Shortly before leaving the U.S., I won a Redverz Solo tent at the Ontario Horizons Unlimited meet. This is a pretty extravagant affair with a vestibule wide and tall enough to garage a motorcycle. It is basically a tall version of the European “tunnel tent” design that you don’t see much of in North America but is all over the EU. I found it heavy and at times awkward to erect. I am quite ambivalent about it. At times it seemed to be sooo big, especially when strapped to the bike. At other times, I loved being able to stand up in it to get dressed. It does allow one to hide a motorcycle “indoors” and do maintenance out of the weather, but a 6-foot tall tent is pretty obvious for camping wild. An undeniable benefit, however, is the ability to pitch it and take it down in the rain without removing the rainfly first. Anyone who has camped in Alaska will appreciate this feature as most American backpacking tents appear to have been designed in places where it does not rain in the morning. Should I spend my own money, I think I will look for a tunnel tent of more modest proportions. This would allow plenty of gear storage and a place to cook out of the weather while still suspending the inner tent from the inside of the rainfly.

I traveled without a hard plan other than a plane ticket to London on August 30th. As it took me several days to ramp up and head north from Lithuania, I had time to go as slow as I wanted and did not mind spending two days at a good camp if I felt like it. I do not use a dedicated GPS but do use downloaded maps on my smartphone for negotiating cities. I had a Michelin map of Scandinavia which covered principal roads but few rural byways. Downloaded maps often did not show the same villages as one another— or the paper map— which sometimes made navigating an adventure in itself. There are thousands of small settlements, villages and outposts. The map identifies one; the sign post at the corner identifies another .

There are a lot of ferries when you try to follow along the coastal route. They connect peninsulas with islands and cross fjords of various widths. Most do not require more than a couple of hours wait, if you are really unlucky, but they significantly impact how far you may get in a day. There are literally hundreds of bridges and tunnels, some of which have intersections and roundabouts in them. The longest is over 27 km., I’ve been told, but the longest one I traveled was about 5 miles. In the north, these are rough-cut inside and a bit like riding through a damp, cold cave. In the south, they are well-lit and lined with concrete. You’ll find them in cities as well as out in the hinterland, as much of the Norwegian mountain ranges abut the sea. The famous Atlantic Ocean Road and its iconic bridge is a long series of causeways and an arcing bridge which is a major tourist attraction. I was told by Norwegians that it makes a better photo than a ride, and this proved true. However, I do not regret having traveled to see it.

Many parts of the world have awesome motorcycling roads. Some you can travel for hours, perhaps a few days. The Norwegian coast is like that, only you travel it for weeks! Imagine the Pacific Coast Highway with tunnels and bridges, going on and on, day after day. I never tired of it. It was breathtaking.

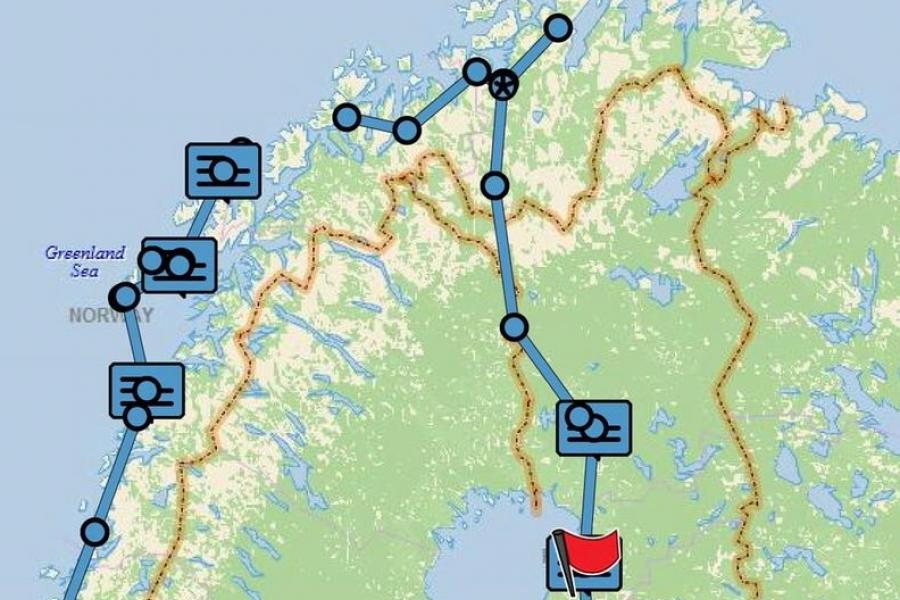

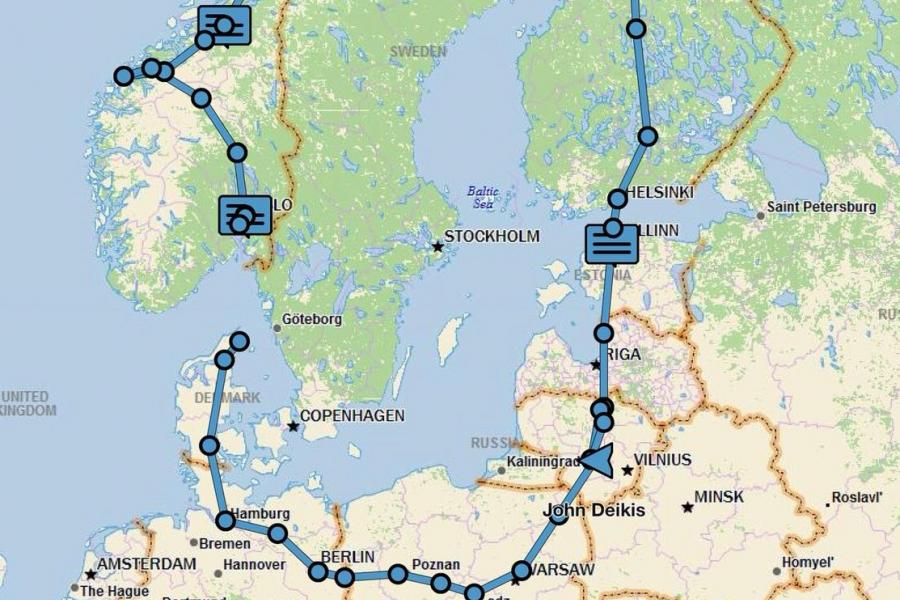

What was my route? Here you go. Mileages appear modest. I either slept late (the midnight sun will fool you into thinking it’s not night time yet), stopped frequently to gaze at the magnificent scenery, or had to wait for ferries— five on one particular day.

After several day-long excursions around Lithuania, I set off for Talinn, Estonia: 353 mi. (camp)

Talinn-Helsinki by ferry: 56 mi. (AirBnB)

Note: There is an “auto-train” from Helsinki to the arctic region that was recommended to me as an alternative to spending the money on gas, food and lodging. During the summer months, it requires several days of advance reservation. Not knowing when I would actually be in Helsinki, I could not avail myself of this option although it could be fun. The ride from Helsinki to Rovaneimi could be done in one day but the “northern Minnesota scenery” can get monotonous and I found Oulu to be delightful.

Helsinki-Oulu, Finland: 379 mi. (camp)

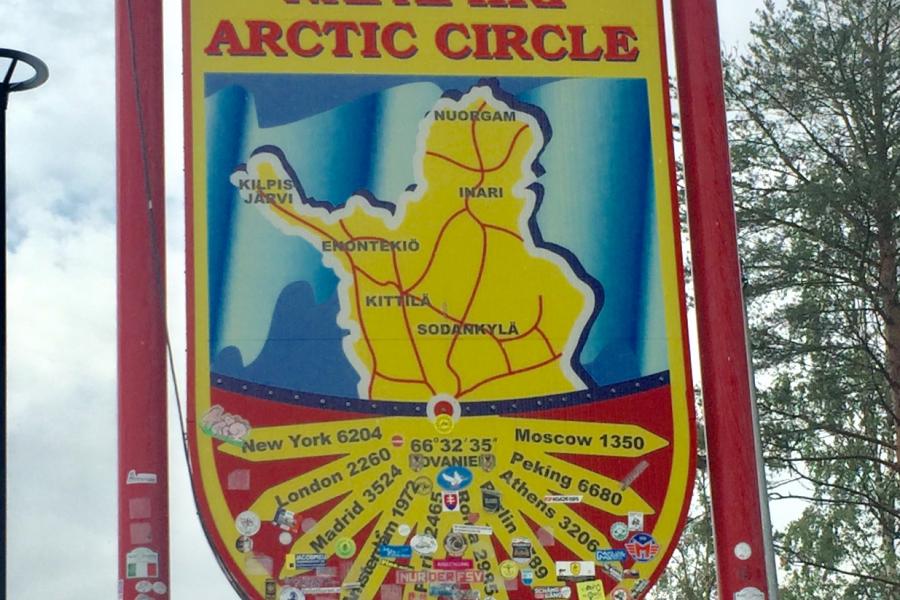

Oulu-Rovaneimi (Arctic Circle and home of Santa Claus): 139 mi . (hostel)

Rovaneimi-Kautokeini, Norway: 247 mi. (camp)

Kautokeini-Alta: 82 mi. (camp)

Alta-Nordkap: 147mi. X 2

Alta-Tromso: 188 mi. (camp)

Tromso-Nordmela: 181 mi. (camp)

Nordmela-Kabelvaag: 120 mi. (hostel)

— Several days exploring the Lofoten Islands —

Kabelvaag-A (yes, just “A”)— near Moskenes Ferry terminal: 85 mi. (hostel)

Moskenes-Bodo (ferry) 67 mi.

Bodo-Reipa: 69 mi. (camp)

Reipa-Somna: 223 mi. (camp)

Somna-Viggja: 229 mi. (camp)

Viggja-Andalsnes via Atlantic Road x 2: 230 mi.

Andalsnes-Alesund via Trollstigen and Geirangerfjord: 173 mi. (hostel)

Alesund-Lillehammer: 227 mi. (camp)

Lillehammer-Oslo: 116 mi. (hostel)

Oslo-Fredrikshavn, Denmark (ferry): 244 mi.

Fredrikshavn-Hamburg: 319 (hospitality)

Hamburg-Berlin: 215 mi. (hospitality)

Berlin-Neuzelle-Konin, Poland: 256 mi. (hotel)

Konin-Kaunas, Lithuania: 404 mi. (hospitality)

Kaunas-Vilnius-Kunas x 2: 256 mi.

The bike used a half-liter of oil in the first 300 miles and nothing thereafter. It used many many liters of gasoline at about $8.00 per gallon. Campgrounds were about $15-20 for a tent site, perhaps $65 for a “hytte” or hut, a cabin without plumbing, about $40 for a bunk or $70 for a private room in a hostel. Half of the time that I did use a hostel, I was the only one in the bunk room, which typically accommodated 4 to 10 persons, occasionally co-ed.

Truckstop cafeterias often had very good freshly cooked food from buffet tables and many convenience stores had kitchens that also prepared food on the spot. Restaurant entres ran $30-45 and bar room beers were about $10. A cold bottle of beer from a grocery store was about $3-5, depending on the brand. This was about the cost of a portion of fresh local fish. Plastic containers of organic salad mix seemed readily available and you could buy 4- or 6-packs of eggs and fresh rolls everywhere. The hostels often had “free food” cupboards where travelers left staples behind. Once I learned to check there before shopping, I usually found pasta, rice, spices, soup mixes, etc. to liven-up my dinners. Every hostel and campground I stayed at had a kitchen available for guests. Showers were large and clean. Some places had saunas. Wifi was ubiquitous, sometimes even into your tent.

I can’t tell you what the trip cost, but I tend to travel fairly economically, sleeping indoors only when I feel like it— which is often determined by the weather. My wife pays the credit card bills, so I should learn about the damage in a month when I get home. AirBnB is good, if you know your whereabouts several days in advance. Couchsurfing was too much trouble. ADVrider’s tent space forum is an invaluable resource but often hosts are not located along one’s preferred route and there are few of them in Norway. My one breakdown was a broken chain outside of Hamburg, Germany and the tent space host I was visiting saved me with garage space and tools for two nights.

The Norwegian fjords and islands are a unique driving/riding experience that I would do again in a heartbeat. The prices are higher than average but it costs what it costs if you want to play. Do it before the dollar falls. Adios! I’m off to England for the Little British Car Co. tour, the Beaulieu Autojumble, the Goodwood Revival vintage races, a bit of exploring in the Cotswolds, and some London tourism with my all-to-understanding wife who has flown over to meet me. Why work?