Chita to Khabarovsk

Elephant destroys a rear tyre in 200km on the gravel roads between Chita and Khabarovsk.5 July to 11 Jul 08

Chita to Khabarovsk is a distance of 2150km. Not much in this vast land. Of this, a few hundred are a bituminous surface varying from goodto pot-hole alley. The remainder, about 1800km, is unsealed. To be more technically correct, the remainder is under construction. To put that in perspective, that is a construction site stretching from Brisbane to Melbourne. In the land of giants, even the construction sites are epic.

Chita, the end of one road at least.

A few dozen riders undertake the 12,000km trans-Russia crossing each year and, with a single ribbon of road crossing most of the land, it is inevitable that each rider will meet, or hear about, most of the others on the road at the same time. The meetings are often short and intense. Each rider, or team, keen to confirm that there are others who would want to do it and desperate for information about the road, fuel, accommodation, helpful contacts and places to avoid.

Most solo riders cover the 2,000km in about five days from Chita to Khabarovsk. We had intended to take six, out of deference to our seniority and common sense, but ended taking five. The story of why is really the story of our crossing.

Trans-Siberian Railway does all of the heavy lifting. It is amazing!

Routes M55 and M58 across Siberia all the way to the Russian East have been poorly built then poorly maintained over many years. The reason for this is that the road system is almost irrelevant to the economy and the lives of the people in remote Russia. It is the Trans-Siberian Railway that provides the all-purpose communications network that binds this impossibly big country together. The railway moves the great mass of every kind of resource or supply, around the clock, with impressive efficiency. Development has followed the tracks with a string of towns clustered along the line and sparse development elsewhere.

The road system has never had the capacity to take much commercial traffic.

The road has been strangely detached from all of this. It moved little freight in the Far East and did mainly local service and was almost impassable in numerous places from time to time. Four years ago work started on redevelopment of the road. The re-surveyed route took it further away from the railway and from the railway towns in many places. The surface varies greatly, but most is now gravel, deep gravel, unconsolidated road-base gravel, riding on marbles gravel, every bike rider's favourite. Gravel!

The road is like riding through a construction site in many areas.

On our way into Chita we met Polish couple Kamil and Izabela riding a Honda Africa Twin. This bike weighs about 50kg less than Elephant, but theirs was heavily laden and would have been no easy ride on the gravel. Our store of up to date information and our confidence grew. A few hours later we met Yasuhito Konishi, solo on an Africa Twin, who had ridden the road three years previously. The road was much harder now, he said. The gravel was awful. Our confidence flagged a little.

Kamil and Isabela on the road to Chita.

Yasuhito looking like he had done it all before.

On the morning of 7 July we solved the riddle of the maze and found our way out of Chita and onto the road east. We had met Charlie Honner, a lone Australian rider heading west, who had given us some good information on conditions so we blasted over the first 100km of tarmac then settled down to the rough ride.

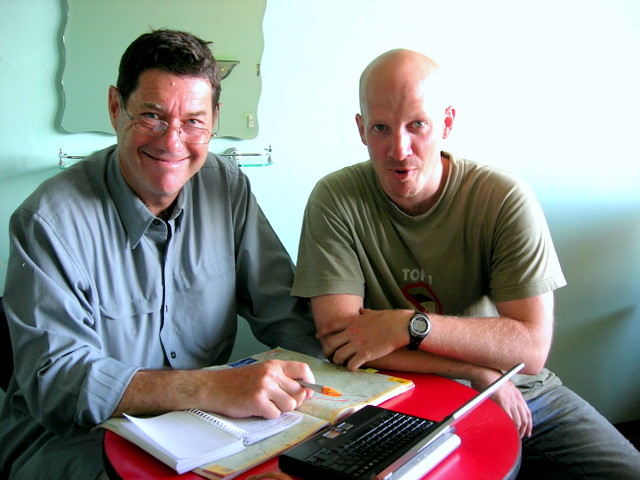

Mike and Charlie in Chita.

For the first two days our ride went to plan. We made the towns we were targeting comfortably and, eventually, found a bed. These towns are desperately poor. Forgotten in the vastness of the Eastern Plains they are ground down by poverty, dusty and frayed. The log-cabin houses have no indoor plumbing at all and are heated by wood fires. No foreigners come here. No tourists get off the train. Nothing much changes.

The guest house in Chernishevsk. It took us an hour to find it. There were six beds in the house. Five were occupied the night we stayed.

A new log cabin house under construction.

We shared our accommodation with ordinary Russians; company reps visiting the small shops, delivery truck drivers, electrical engineers working for the power company. We ate in their cafés, discussed the road and the weather and answered, as well as we could, their ever curious questions about where we had come from and why we were there. The Russians we met started to have faces and names, jobs and families.

A typical roadside café where the weary traveler can get a bowl of cabbage soup (and other stuff).

On a dusty section of road we saw a couple of big bikes approaching and pulled Elephant over for a meeting. As they emerged from the dust we saw that they were all Harley Davidsons, all low slung cruisers. There were 17 in all from the Korean chapter of the Harley Owners Group! They had a support vehicle for all their gear with a trailer behind that had a bike on it.

The Korean HOGs looked like they had had a big day out.

The HOGs were on their way to Germany on a grand adventure. They had had some bike problems and gathered around our heavily laden rig looking at the details of the luggage fit, the special knobby tyres, the long travel suspension and lots of other stuff. Elephant looked down that funny nose at the low slung cruisers and I must admit that I saw a certain rugged purposefulness in the beast that had eluded me on the freeways of Western Europe. Out here, Elephant looked the goods.

Mike signed the leg of several HOGs. This chap already had a dozen signatures!

On the third day it rained, and rained, and rained. We met Masayuki Goto on his Africa Twin looking cold and tired but showing the same sense of independence and determination we see in all the riders. We reassured him that the road ahead was awful and he did the same for us. It seemed the least we could do for each other.

Masayuki Goto in his rain gear.

The road turned to mud. Elephant slipped and slid and we were reduced to a 2nd gear idle. It took three exhausting hours to cover 40km. There was nowhere to stop so we pressed on throughout the day and into the early evening. We stopped for fuel in the early twilight and learned that there was a hotel in the town of Skovorodino not far up ahead. We set out to find it.

At least in the rain you can see the potholes before they crump your suspension...

...in the dry they just can't be avoided.

30km further along we found the sign for the turn-off to Skovorodino. It was one of those large white on blue signs and said turn in 300 m. We turned. The road went 25m and stopped dead. We went down the highway further, turned around and found a sign coming from the other direction. Turn in 200m it said but the side road remained a 25m dead end. This was Russian humour at its best and even after 12 hours on the bike in the rain we got the joke.

Mike starting to look like the day had gone on too long.

We continued east for another 16km wondering where we could find a bed before seeing a small track heading off in the direction of the town. It had no sign post but we followed it anyway. After about 10km a town of 30,000 emerged from the mist! The joke, it seemed, was on them. We had found Skovorodino.

We also found the hotel, a clutch of friendly, helpful locals who manhandled Elephant up the hotel steps and into the foyer, and a Chinese restaurant that didn't serve rice but did serve chips.

The road dried out on the fourth day and we made better time sometimes going as fast as 40 or even 60km/h! The day was hot and long, food and fuel were hard to find and there was no sign of accommodation in the place we had hoped it to be.

We pressed on further. The second accommodation option we had planned failed to materialise and, with the last of the afternoon shadows fading and only the twilight left to ride, we had 170km of bad road to the last option. We pressed on with some determination over some of the worst roads we had ridden. We made the distance just after last light to be told by the locals that there was no hotel or guest-house for a long way in any direction. Our information had clearly been wrong three out of three!

The roads in this section were very hard to ride. They were a sand base with loose river gravel up to 100mm deep. If Elephant wasn't skating on the stones, the front wheel was burying itself in the exposed sand.

We had dinner at a roadside café and headed Elephant east again on a stretch of sealed road. After about an hour in the saddle we found a small side road, then a track and finally a concealed meadow. It was midnight and we had been riding for 16 hours.

We organised an improvised shelter and settled down to get a few hours sleep in our stealth camp. Unsurprisingly we both slept well!

Stealth camping was not on the plan but we were prepared for contingency.

We had a dingo's breakfast and started early on the fifth day. The road got better, then worse, then better again. We met Edgar from the Russian Black Bears Motorcycle Club when we had only a few km of unsealed road remaining and he had the whole ride to Moscow ahead of him. We wished him luck with some sincerity. Then finally, late on the afternoon of 11 July we ambled into Khabarovsk and booked into a hotel with plenty of hot water and a double bed.

Edgar was solo on a light bike.

Throughout our 12,000km ride across this stunning land we have rubbed along with the ordinary Russians going about their lives. In the remote areas the only foreigners have been other adventure riders. The locals have been friendly, amazingly helpful, curious, cheerful and pleased that we have made the effort to come to their town.

The road stretches into the vastness of the Russian Far East. Khabarovsk is somewhere out there!

Long distance truck drivers in this place have a tough life. The extraordinary distances, appalling roads, extreme climate and almost complete lack of infrastructure make every trip an adventure. They form a sort of tough-guys brotherhood, proud of the difficulties they face each day. We have had many conversations along the way with them speaking Russian and us speaking English. They give us advice about the road ahead, the weather, where to get a bed and the cafes where the cabbage soup is as good as grandmothers (at least that's what I think they said).

When they see the bikes, with their grim faced riders skating around on the gravel, they acknowledge them with a series of horn blasts and a friendly wave. Some punch the air with a clenched fist in the universal salute of the undefeated; the exclamation mark of defiance.

We always acknowledge them with a wave and, I have to admit, occasionally a raised clenched fist. After all, we are all tough-guys out here.