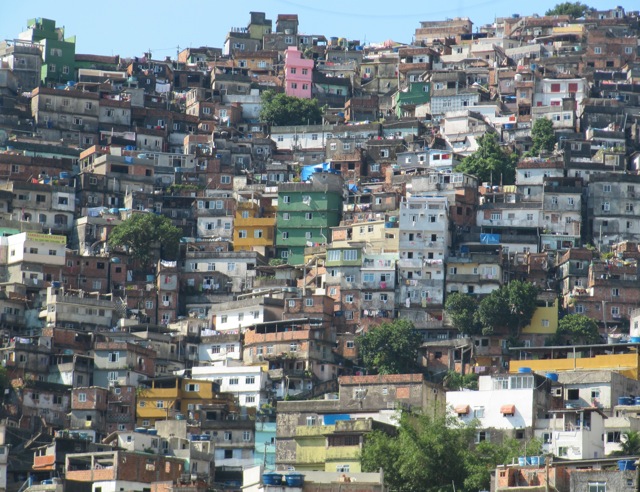

The Favela, Rio

We booked ourselves on a trip to see the largest favella in Rio, Rocinha. We wouldnt usually for the organised group tour, but an unguided stroll through a Favella of some 250,000 inhabitants, policed and run by machine gun toting drug lords and narcos didnt hold much appeal either. We booked ourselves on a trip to see the largest favella in Rio, Rocinha. We wouldnt usually for the organised group tour, but an unguided stroll through a Favella of some 250,000 inhabitants, policed and run by machine gun toting drug lords and narcos didnt hold much appeal either.

We were picked up by a mini bus, and joined a group totally 14 or 15 other gringo tourists, eager to catch a glimpse of life on the hillside residences that peered down onto the white sandy beaches and high rise condos of the more fortunate Cariocans.

Roughly 19% of the 6million Cariocas live in the favellas that hang precariously on the hillsides around the city. They are the blood that runs through the veins of the city. They sell coconuts to beach goers, wash dishes in the glitzy hotels and restaurants, they shine the shoes of the businessmen, the relieve tourists of their cameras, and supply the drugs to the party set and dope smokers who ride the waves on the pristine beaches.

The beach at the bottom of the Dois Irmaos mountain

We were driven to the foot of the Two Brothers or Dois Irmaos mountain, from where we all climbed onto the back of local moto taxis, and driven through the favella to the top of the mountain, under strict instructions to put our cameras away and hold on tightly to our bags and the driver.

We re-grouped at the top and were given a brief talk about the history of the favella.

The shantytowns first sprung up in Brazil after the abolition of slavery in the late 1800s. Rocinhas history dates back to the 1920s, when the depression spurred on a massive migration of country folk to the cities. The growth accelerated in the 50s when several smaller, surrounding favellas were demolished by the government in order to make homes for the growing community of wealthy Brazilians.

the view from halfway up the mountain

Over time, the wooden shacks were replaced with concrete and brick, with homes being built literally one on top of the other, sometimes up to nine stories high. The land being built upon was, and still is owned by the government and is part of Rios national parks network. Most of the residences, and in turn their inhabitants live there illegally, under the radar. The water company runs water through the favella for half an hour in the morning, and half an hour in the afternoon, and the residents who are not plumbed in directly to any source of water go out to the street and collect water from the pipes.

A few of the residents have addresses and are registered, giving them the opportunity to vote, but the vast majority simply dont exist.

We began our walk through the heart of the favellas, our guide occasionally going on ahead of us to let the spotters who were on the lookout for police that we were approaching, giving them the opportunity to hide away their guns, and giving us the chance to take out our cameras.

Children played happily in the narrow streets, running up to us and posing for photos or showing off their drumming skills on plastic bottles and old paint cans. The favelados we met were all welcoming and friendly, with the exception of a few gaunt, lanky men, whose necks were adorned with more gold than Mr T. They looked us over suspiciously while inhaling deeply from their joints.

Overhead, the electricity poles had a stupendous amount of wires twirling off in every direction. A few residents had electricity supplied directly to their homes but the majority simply ran their own cables from the poles, tapping into the supply in their own inimitable way. Their supply was rarely constant, but it was certainly cheap.

DIY Electricity supply in the Favela

We were shown around one of the many NGO projects in the favella, an art studio where local artists displayed their work, and a bakery where young favelados where taught how to bake bread and cakes.

Our guide seemed to know the name of every child we came across, and told us how he had seen the favella become safer and safer over the last decade or so.

The narcos still held the power in theses neighbourhoods, and much like the East End of London under the rule of the Kray twins, they kept the peace as well. There was very little crime in the favellas. Mostly because no one really had anything to steal, but also the narcos wanted to keep the favellas safe so that the tourists would come and drop some cash here and there, and also to make it safe for their business, to sell drugs.

We were fortunate to have a dry day on our visit to Rocinha. There is no rubbish collection, instead the inhabitants let nature take care of that, leaving their rubbish for the rain to take down to the bottom of the hill and dump the residue on the beach below.

With no trash collections in the Favela, gravity and rainfall take care of removing the debris

I was invited into one of the homes on the hill, and was shown to a window that offered a view of the condos and the beach below, less than 1 kilometre away. I could only imagine how painful it must be to wake up each morning in the tiny crumbling house, home to a family of 6, and look out of the window to see that unreachable dream. So close, yet so very, very far away.

We left the favella and half an hour later we were back on Ipanema beach, buying sarongs and handmade bracelets from the very same people we had just been visiting in Rocinha.