The Elephant and the Super Highway (Originally posted 17 August 2014)

Country

Roads: old, new, rough tracks, super highways, wet or dry, they are at the core of a motorcycle journey. For Team Elephant, they have an almost mystical importance. We have looked for the best mountain road in the world in the European Alps, ridden the best sweeper in the world in Morocco and hammered ourselves for days across the endless corrugations of the Amur Highway in Siberia. Without the roads there would be no journey. Without the roads there would be no Team Elephant.

For many of us who came of age in the 1950s and 60s, America's roads and the cars that cruised them came to define the country itself. For those of us learning to drive in underpowered cars on goat-track roads, the image of American V8s on sweeping super highways was enchanting. It was the stuff of fantasy and I remembered those fantastic images from my youth as we drove our hire car up Interstate 5 north of Los Angeles heading for Atascadero.

I remembered it again as we passed under the I-5 on the back roads a week later riding Elephant across the California Central Valley looking for the twisted remnants of the old routes through the Sierra Nevada that were the antithesis of an Interstate. We could see the mighty road five miles away across the valley with its endless lifeblood flow from the Canadian border to Mexico.

So compelling is this image of America that it is easy to overlook the simple fact that the highway system is a relatively new development and that it was not the road system that opened the country. After an initial flood of migrants west on the overland wagon trails, it was the early and dramatic expansion of the railways, and the expansion of the navigable rivers with a system of canals, that carried the burden of uniting and developing a new nation. Americans roads were so poor that in 1919, following WWI and propelled by the concern of military planners, an Army expedition was mounted to test how difficult it was to drive across the country. The expedition included Major Dwight Eisenhower who was recently returned from service in WWI. The journey took 62 days and claimed nine of the 79 vehicles in the convoy. Twenty one of the 276 expeditioners were also lost along the way. The journey had a profound effect on the young Eisenhower.

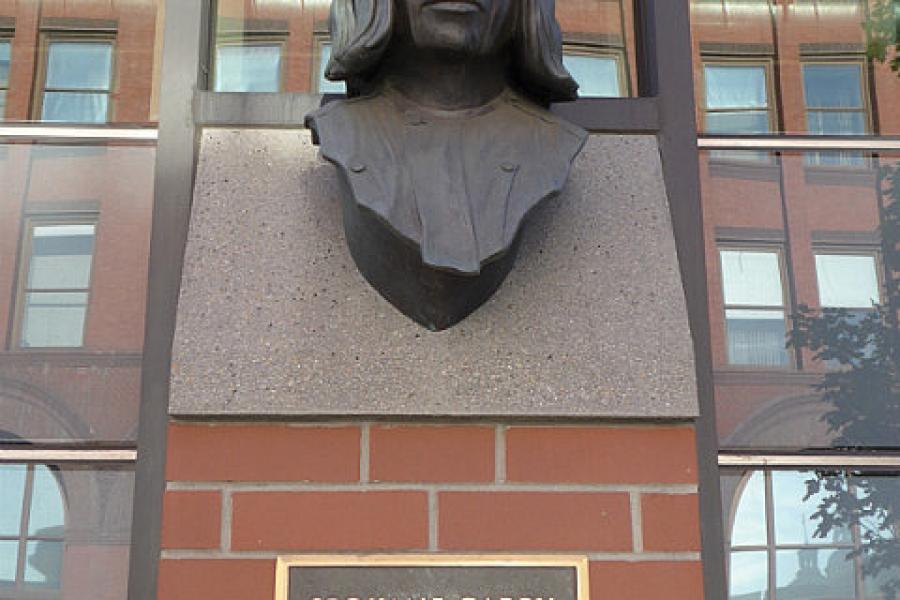

About the same time, a little known Iowa bureaucrat named Thomas MacDonald was plucked from obscurity to be appointed Secretary of the Bureau of Public Roads, a position he would hold for the next 36 years. MacDonald was an iron willed, curmudgeonly martinet, but he was also a visionary and tireless administrator. It was MacDonald who devised the plan for a network of national highways, convinced President Roosevelt of the importance of the project and had it included in the New Deal. Today, few Americans would recognise his name.

War and retirement stopped MacDonald from seeing his grand vision implemented but he was its instigator and designer, devising the naming system for the roads and allocating the numbers. This includes the number 66 given to the road from Chicago to California and made famous by John Steinbeck in his novel The Grapes of Wrath and later by the Rolling Stones in song. Even here, history had a funny twist. This famous, but now defunct, road was originally designated No 60. This changed when Kentucky complained that their road would be designated No 62 which seemed to Kentucky an inauspicious number. After complaints from the governor, MacDonald resolved the impasse by giving Kentucky road No 60 and the Chicago-California road the unallocated number 66. It was just as well, get your kicks on Route 60, just doesn't sound as good!

The last twist of the story is that when Dwight Eisenhower became president he signed into law the means to fund and build the national highway system designed by MacDonald and Roosevelt. And, it is an amazing system. There would come to be 41,000 miles of highway with the longest, the I-90 running 3,020 miles from Seattle to Boston without a single traffic light. It is truly one of the engineering marvels of the world.

None of this, interesting as we found it, was sufficient to entice us to steer the Elephant onto the I-5 or any other Interstate. We wound our way north through the mountains on the little used back roads. The pictures and captions tell the story of our week but by Sunday the 10th of August, we were in Spokane Washington planning our route to Canada without using a single mile of interstate but at least remembering the remarkable man whose vision and design helped to shape modern America.