Rich Days and Poor Days (Originally posted 26 Oct 2014)

Country

Charleston, Old Charleston, is a wonderfully preserved and historically important city in South Carolina. Our friend Ian is a Charleston native and we could have had no better host for our visit. Ian knew the history of every building in the old town. Indeed, his own house had a wonderful history. It was built from Bermuda Stone which was limestone blocks that came to South Carolina as ballast in ships. The house was also, reputedly, once the dwelling of Black Beard the notorious pirate. I think Ian was a little bemused at my delight in this small fact. But imagine, living in a pirate's house! How many folks could claim that!

For Jo and me it was a special treat to catch up with Ian who we had first met in a small village on the edge of the Sahara in southern Tunisia. It was also a much needed and relaxing break from our travel schedule. Inevitably, it was over too quickly. By then, we could go no further east, the Atlantic Ocean having gotten in the way, so we turned back towards the west. We had settled into an easy rhythm on the road and romped into the back-blocks, on the narrow “C” roads, losing ourselves in an America we often struggle to understand.

As the months have passed the conversations and observations that are the grist of our curiosity have multiplied. They are diverse and seemingly contradictory. In a small cafe by a lake we met Peter and his pitbull terrier and started a conversation. Our foreignness was of little interest to him. He asked no questions but found us a safe audience. He had a motorcycle and that was our connection. Peter made some money cage fighting but I sensed he mainly drifted around on his motorcycle hoping some opportunity would come up. He took no benefit from the government. He hated the government. He was well armed because, he said, there is a revolution coming and he wants to be prepared.

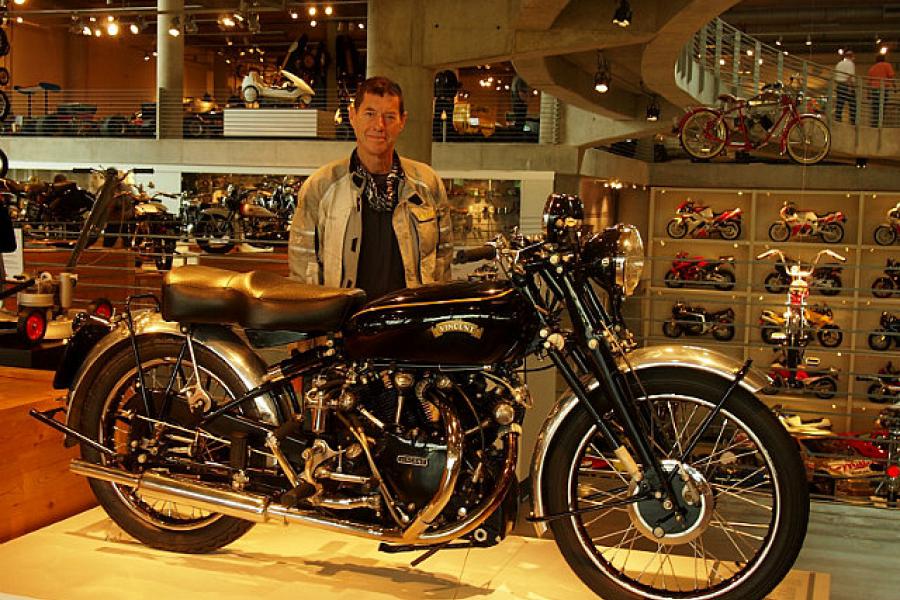

Two days out of Charleston we arrived in Birmingham Alabama for a pilgrimage to the Barber Museum which is the largest, and arguably best, motorcycle museum in the world. I got lost for a day among the machines that fired my imagination as a boy too many years ago to think about. The photos tell the story of a place worthy of the effort required to get there and it is an effort that every self respecting motorcycle enthusiast should make.

In a motel carpark a the couple in the next room struck up a conversation when they saw us standing by Elephant. They were thin, perhaps gaunt, her hair was grey and braided, their jeans worn but clean and the practical fit of their shirts and work boots left no room for compromise. They had 40 acres in New Mexico and kept a few horses. They had no electricity and collected rain water. I could visualise the block as one of thousands of similar holdings we have seen in Colorado or Nevada or Arizona, each with its poor dwelling and collection of broken things and broken hearts distributed across the plains. They had been waiting for their old truck to be fixed so they could head home. The problem with America, he opined, is that a few people have all the money and everyone else just gets screwed. Who really needs a billion dollars, he asks. No one, he says, answering to his own question.

I guess it was inevitable we would go to Memphis. I mean, why wouldn't we? Actually, there are several reasons including the dreadful tourist trap to which Beale Street has descended, but our misgivings were unnecessary. A couple of blocks away from the tourist strip a threadbare working city was packed with enough history and interest to keep us exploring for a couple of days. Having decided to spoil ourselves with a special dinner, we found a little brew-pub with food so good we went back the following night. My favourite was the shrimp and grits; we both enjoyed fried avocado with tapenade and the duck confit fried rice was a real find; all better than they sound.

In a supermarket carpark a neat man, fit for his age, came to investigate our arrival and we started a conversation. The veteran was as conservative as I assumed he might be, but also a man of compassion. He was worried about the country he fought for. The poverty and hopelessness worried him most. We waste so much money, he said, that we can't afford what we need. He goes on and asks why “they” give money to people who don't work, why there are so many social programs draining the budget and why the workers are treated so poorly. I took it as a rhetorical question and didn't reply.

Buoyed and encouraged by our stop in Memphis, we decided to try our hand in the Ozarks and set off for Arkansas. We found the mountains, coconut pie and a few mountain roads barely worthy of the name.

A waitress in a diner served us breakfast and we started a conversation. She earned $3.50 an hour plus tips. How can that be, I asked, isn't the minimum over $7.00. That's right she said. If my tips and pay don't add up to $7.50, the owner must make up the pay to that amount. She saw the surprise in my face and asked how much she would earn in Australia doing the same work. Because it is a Sunday, I told her, it would be a little over $40 an hour plus 12% additional paid into superannuation. I could tell from the look on her face she didn't believe me and I resolved never to answer that question again. Anyway, she said, almost as a exclamation mark behind our conversation, I love my country.

We spent a night poring over the maps. We had friends living in Leavenworth Kansas whom we hadn't seen for 20 years. We couldn't pass so close without seeing them so we checked the weather and calculated the chances of getting to Leavenworth then across the plains before the next turn in the weather. It was doable.

We rode past a lakeside, gated community of two storey mansions surrounded by a suburb of demountable houses (mobile homes they are called here) each with its collection of broken stuff in its yard. The same scene was repeated many times in many other places. After a while we didn't mention the dissonance. After a while the shock of the contrast was gone but behind it all some things were clear. The US has become a more polarised and divided country than it was when I first drove across it more than 30 years ago. That polarisation has a hard edge and we rub against it every day. Wealth is less evenly distributed, the middle class is shrinking, a tiny number of individuals control half of the country's wealth. A small number the vast majority. Janet Yellen (Chairman of the Federal Reserve) has said that this problem is a risk to the fabric of the society. One study published by the New York Times claimed that 95% of the benefits of the recovery since the GFC has been gained by only 1.0% of the population.

The problem, according to a man in a service station who feels we are kin because he has a Harley trike, is welfare. This, he says, is the land of opportunity and too many hand outs just stop people making their own fortunes. Envy of the wealthy is just a ruse to divert attention from those who want to live on benefits. The liberals are the problem. I said nothing. Later I wished I had simply told him that he was wrong. Still later I was glad I had said nothing.

The level of opportunity in a society is measured by its level of intergenerational mobility. That is, how likely is it for a man (no complaints from the ladies please) to do what his father did for a living. The more opportunities in a society, the more likely a man to do something different. I found the data on this late one night in an espresso-free town in southern Kansas. The only OECD country with poorer intergenerational mobility than the US is the UK which still has vestiges of its class system. It is, like all such data, a blunt measure but what is undeniable is that countries with the most even distribution of wealth do best in providing opportunities for their citizens. For many the US is still the land of opportunity but for others opportunities are few. We pressed on into Kansas, as always, “workin' on mysteries without any clues...”