The Colorado Plateau (Originally posted 8 Nov 2014

Country

The Colorado Plateau, all 337 000 square kilometres of it, rises up roughly centred on the junction of the four states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico. It was pushed up three kilometres from below a great inland sea about 75 million years ago by the same forces that formed the Rocky Mountains but, unlike the mountains, has remained geologically stable. The Ice Ages, starting about two million years ago, provided a wetter climate that greatly increased excavation of the sedimentary layers of the plateau and by 1.2 million years ago the canyons and the Colorado river system were much as they are today. The unusual geological stability of the Plateau has resulted in one of the most complete and studied rock sequences on earth with 40 exposed sedimentary layers, as well as igneous intrusions and deep metamorphic strata which have provided a base to the canyons and shaped the weathering of the softer rock.

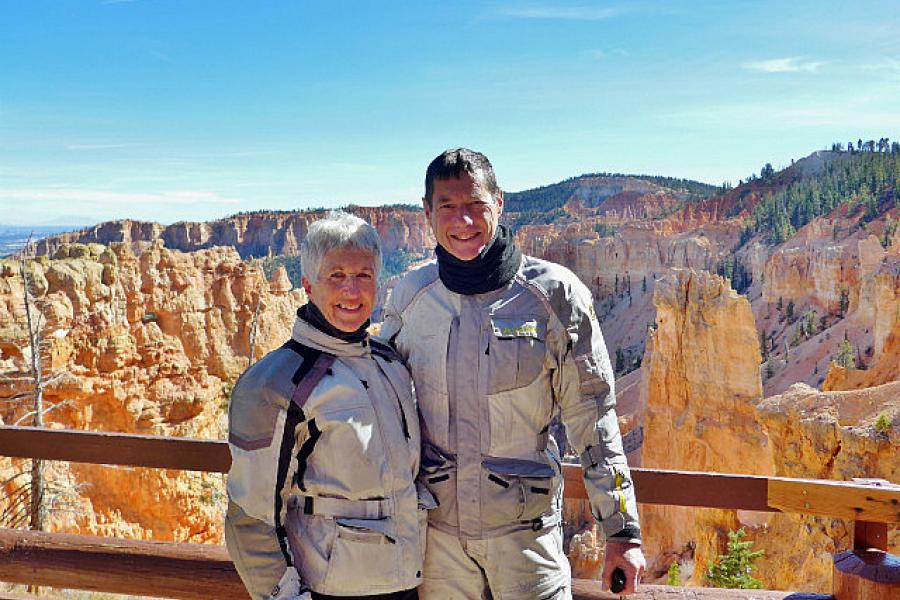

The Colorado Plateau contains eight National Parks, including that of the Grand Canyon, and 17 National Monuments. It is an amazing concentration of natural beauty and a credit to the US that so much of it has been preserved. From our climb onto the east of the Plateau and visit to our first plateau park at Mesa Verde, we charted a wandering course north into central Utah then south and finally west to exit the Plateau near the Arizona-Nevada border. For Team Elephant it was two of the best weeks we have ever had on a motorcycle; two weeks of stunning natural beauty, perfect weather and relatively deserted parks. Even the South Rim of the Grand Canyon was free of the usual crush of tourists. We had the North Rim much to ourselves.

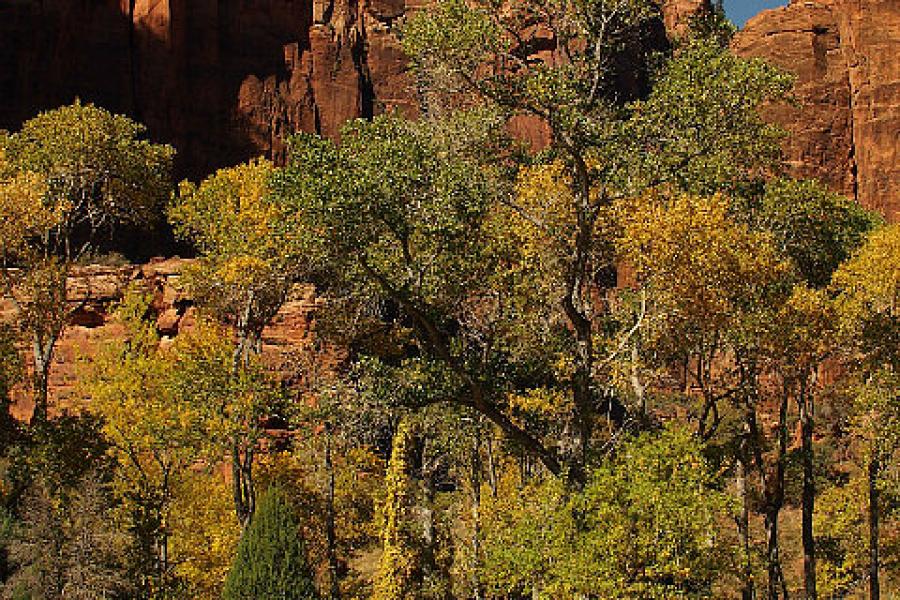

The photos and captions tell the story of our visit better than our superlatives but be assured that the best of our camera work is a pale representation of the original. We have often been underwhelmed by famous places we have visited. The hype is often well beyond the reality. But here... well, here you can stand in childish, slack-jawed amazement on the edge of a precipice and not feel embarrassed by your welling enthusiasm in the least.

The US National Park Service is a national treasure. It does a sterling job of balancing the stress of thousands of visitors with preservation of the parks. One of the facilities it provides is an excellent information centre for each of its parks. We always visit them and often find much of interest. In the parks on the Colorado Plateau we quickly noticed that one name appeared repeatedly. Quotes from John Wesley Powell, who led the first scientific expedition into this part of the country, were featured in each display. The quotes invariably came from Powell's own record of that 1869 expedition: Exploration of the Colorado River and the West.

We already knew a little of Powell from our research but he was such a powerful figure in the history of these National Parks that he seemed worthy of a little more attention. A quick survey of a bookshop turned up four monographs on Powell from which we selected one by Wallace Stegner who had authored several other works we had enjoyed. It was an excellent choice. The Wes Powell who jumped from the pages of Stegner's work was much more than the intrepid expeditioner we had expected. In many ways, Powell was an archetype of those 19th Century titans who raised themselves from humble beginnings to create a great nation; another version of Lincoln had he chosen the law rather than science as his passion.

Wes Powell's parents were barely off the boat from England when he was born, the son of an impoverished itinerant preacher. His family moved west to Illinois where he grew into the gruelling life of small-hold farming and where, against the specific wishes of his overbearing and over-religious father, he developed an interest in the natural sciences. Powell was both a polymath and an autodidact working 15 hour days and still finding time to acquire books and read widely. In many ways, however, the more important part of his education came from years of incessant travel along the boundaries of the then known continent.

Powell had strong abolitionist sympathies, voted for Lincoln and volunteered for the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War. He rose to officer rank in a few months and lost his right arm at the battle of Shiloh. This didn't seem to slow him at all. He continued to serve serve and rose to command the artillery of the 17th Army Corps. After the war this self-taught scientific enthusiast took up a professorship of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University at Bloominton and quickly manoeuvred himself into the position of Curator of the Illinois Natural History Society. It was from this position that he was able to assemble and then lead the first scientific expedition down the Colorado River and record for the first time something of the fantastic west.

The expedition was legendary. The one-armed Powell was a superb leader; intelligent, heroic and indefatigable. His account of the adventure brought the spectacle of the West to public attention for the first time. His reports also proposed that the arid West was not suitable for agricultural development, except for small areas where irrigation systems were needed, and that state boundaries should be based on watersheds to avoid water disputes between states. If this had been the extent of Powell's achievements he would remain an important figure in the opening of the newly acquired West. But for Powell this was only the beginning.

He turned his attention to Washington, proved himself an able political operator and was appointed the second director of the US Geological Survey, a post he held until 1894. He was also the director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institute. It was from these positions that he was most effective in shaping the way US exploitation of the West would be played out. His views on the West were in stark contract to many orthodoxies of a time when the nation was gripped with the idea of “manifest destiny” and all obstacles to western settlement were swept aside in the greedy rush to find new fortunes. For the first time, Powell brought scientific rigour to the debate about the settlement of the West and moderated the worst excesses of the exploiters. His rational pragmatism and innovative ideas were years ahead of his time and many of his plans were not fruitful for another hundred years.

The most impressive thing about Powell, a man with many impressive facets, was his ability to meld his frontier education and tireless drive with skilful political manoeuvring to achieve practical ends. Indeed, Powell's frontier education and pragmatism were so central to his character and success that it is unlikely any other background could have produced such an effective bureaucrat and scholar or such a beacon of the Enlightenment. I am not sure what lessons there are in Wes Powell's life for us today but as I watch the US mid-term elections play out I can't help but think that a little practical experience, some science and a few facts might not be a bad place to start if the current generation wants to be remembered as fondly; that and a little 19th century optimism.

Notes:

For more on John Wesley Powell: Wallace Stegner, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, John Wesley Powell and the second opening of the west, New York, Penguin, 1954.

The map I have included was lifted from the following paper: The Colorado Plateau Region, In Wilderness at the Edge: a citizen proposal to protect Utah's canyons and deserts, Utah Wilderness Coalition, Salt Lake City, 1990.