Barranca Del Cobre

Riding into a dense fog that slowly lifts with the sunrise hour, Katie and I head out of Concordia and climb the Sierra Madre Occidentals towards Durango, 200 kms to the east. From there it will be another 600 kilometers north to the last major destination on my "must see" list: Barranca Del Cobre, or Copper Canyon. EyeWitness Travel Guide states, "Bigger by far than the Grand Canyon, yet nowhere near as well known, Mexico's Copper Canyon region is one of the great undiscovered wonders of North America."

As we switchback up the Sierra Madres we punch through more layers of grey. It swirls around Katie and I as we cross the Tropic of Cancer. The crossing ceremony consists of the GPS beeping the arrival of 23° 26' 22" North. I look around. Nothing but dense fog, dark green bush and mountain passing by. Not much of a celebration but still, another milestone.

As the morning sun gathers strength the fog dissipates and we climb into sunshine. At one of the last westward viewpoints it's time to stop for one more look at the Pacific. Blue sky builds in that direction. Another stellar day for Mazatlan.

Looking east it is plain I will be climbing into more weather. Highway 40 to Durango is not without charm, although much becomes lost as we ride in and out of more cloud and fog. At El Espinazo del Diablo (Devil's Spine), the road crosses a nine kilometre narrow bridge of rock with near vertical drop-offs on both sides. A damp, chill wind blows dark clots of mist across the exposed ridge as I stop to examine the place. I hurriedly put on warmer clothing. Taking a photograph of shifting shades of grey and green seems pointless. As I go to leave this neblina windtunnel, Katie's hydraulic clutch system fails. Again. The oil pressure has dropped from the mystery leak and the clutch won't engage. In what is becoming a ritual, I remove the reservoir cap and add a teaspoon of 10 wt. mineral oil. I'm not used to being cold and my hands shake, but in a few minutes I have a clutch again. Within an hour Katie and I summit the Occidentals and start down the eastern side. El Sol warms our road ahead and with it my mood.

At Durango we turn north. This is Wild West country and home to many Hollywood dusters of John Wayne and Sam Peckinpah fame. More recently, classics like 'The Mask of Zorro' with Antonio Bandaras and Catherine Zeta-Jones were filmed near here. Just past the pueblo of Chupaderos, Duranago's most used Hollywood location, another western classic stalks us from the northeast. A mature cumulonimbus towers to the stratosphere and sends long black streaks of rain thundering into the dusty ground. Katie and I take cover under a Pepsi stand in a tiny poblado.

That evening, after dodging a few more CB's, I find a quiet place to freecamp among the junipers and thorn trees that line the road to Parral. I wait til no one is in sight then head down into the ditch and drive into the forest. Out of view from the traffic of Highway 45, I hide in the trees and wait for sunset to set up my tent. Time for a Nicaraguan cigar and a 600 ml bottle of Coke. As I sit contentedly in the short grass, I watch the moon rise full with the setting of the sun. It'll be nice to camp again - last time was high in Los Andes of Peru. The night passes as quietly as the moon.

From Hidalgo del Parral , home of Pancho Villa, and location of his infamous assassination on 20 July 1923, Katie and I head west then north towards Barranca Del Cobre. The ride is pleasantly scenic as the two-laner blacktop meanders through hill and dale. Just what the doctor ordered.

Copper Canyon actually refers to not one but 20 canyons carved out of the Sierra Tarahumara by six different rivers. Together, these canyons create an area four times larger than Arizona's Grand Canyon. At an altitude of only 1640' asl, the canyon's deepest point (Barranca de Urique) has a subtropical climate, where banana, mango and orange trees grow, while the peaks above reach 7500 feet and are home to bushy conifers and evergreens. One of Mexico's most numerous indigenous peoples, the Tarahumara, still retain a traditional lifestyle here. Perhaps one reason for its anonymity is the Cañón del Cobre remained inaccessible to the casual visitor until the early 1960s.

The descent to Batopilas consists of a narrow 60 kilometer road of dirt and embedded rock carved out of steep canyon walls. It snakes down over a mile in depth with switchbacks so tight I must stand on the pegs and negociate the hairpins in first gear. Short sections of road allow for second gear. Such charming engineering features as bridges without railings ensure I pay attention to driving not sightseeing.

What with photo stops and a snack break, it takes me five hours to reach my subtropical destination of 1100 inhabitants. Batopilas, established in 1690, is built either side of its one street, hemmed in between cactus-studded canyon walls and a muddy swirling river. Standing alone just a mile upriver from town is the classy Hotel Marguerita. For 250 pesos a night ($23) this beauty wins my award for most romantic, best value for money, and best location with a view. Dressed in riverstone and white plaster, with open beam ceilings, stained glass windows and rooms with brass four-poster beds, the place exudes quiet luxury.

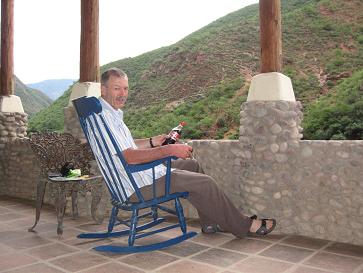

My second story room walks out on a spendid verandah from which I have a view up and down the canyon with the rio almost at my feet. I hear nothing but the hum of cicadas and the flow of the river. I am the only hotel guest as the August heat discourages tourism. High season, and much higher prices, is November to February. On my shady verandah-for-one a royal blue rocking chair invites. I accept and settle in. Time to watch the world go by. Time for a cigar and a cool cerveza. Batopilas being a dry town, I settle for a cigar and a Coke.

Across the river, heading upstream, a Tarahumara family walks by, perhaps 150 yards away. They follow a footpath that might be, like the dry-stone wall beside them, 300 years old. A burro leads, heavily laden. Next follows the man, white cowboy hat, like all Mexican men wear, with tan shirt and black pants. He walks with the help of a long crooked staff. Next the boy, about 10. He carries a hefty burlap sack on his back. Finally the woman comes into view, long black dress, white blouse. In each hand she carries a white plastic grocery bag. She walks tired. They file past then are lost from view in the trees. I watch as they reappear from time to time. A bend in the green canyon and they are gone.

A vaquero rides by on his burro, following the same camino antiqua. He makes good time as he too heads upstream for home. Downstream a few hundred yards, a modern burro, a white Toyota Tacoma, wades across the river, fender deep, delivering a white hatter to his casa on the far side. A black bird of prey does a low and over the truck then, with occasional flaps of his big wings, continues upriver to land on a midstream boulder the size of a cottage.

Further upstream, to the north, a moody black sky flashes and rumbles. As Dave Clark would say, sounds like the Gods are bowling again. My cigar smoke drifts lazily. Nothing, it seems, except the river, is in a hurry in this ancient land.

Darkness settles, carried in by the approaching storm. Below me, on the muddy road, sits Katie, snug under her cover. Bathed in a Hallowe'en glow she sits beneath the only yard light in my part of the canyon. Time for bed for me too. As I enter my room, strobes of light, bright as day, flash through the stain glass windows from the lightning and I hear the patter of rain start on the roof. A breeze billows the curtains. It's going to be a hell of a storm. I sleep well tonight.