La Rioja Province

We explore La Rioja province by a loose connection of zig-zags and driving in semicircles. Fine by Joyce, not taken to artifical rules, but not typical behavior for the guy side of the equation. But really, I must admit, we don't have a destination either.

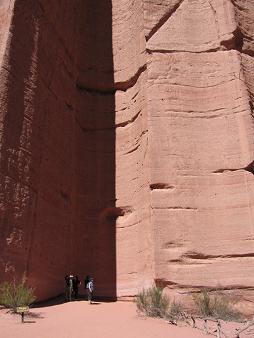

Within the canyon of red 500 ft sandstone cliffs in Talampaya our tour group gathers at the base in a scuptured chamber. In unison, our group shouts "Hola!" Our first echo bounces back almost as loud. We laugh in surprise and the canyon echo immediately mimics our childlike laughter.

Talampaya National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, contains Triassic period dinosaur bones, centuries old petroglyphs from early indigenous; a botanical garden of local flora and a bunch of critters, including guanacos, hares, maras (looks like the love child of a rabbit and guinea pig), foxes, condors, and Miss P's favorite, armadillos.

We have seen hundreds of these guys in the wilds of Patagonia, where, like here, the guanacos are protected. They are also one of the camelids that never took to domestication. They don't take kindly to pumas either, their only enemy.

As we return near sundown from the five hour tour, we spy dozens of armadillos near the road, shuffling and snuffling along the desert floor. Looking far too busy peering down holes and checking out scrub brush for food, these mini-me armoured tanks don't have time to look back to see if we're looking back at thee.....

At the end of an interesting but dusty day touring the canyons of Talampaya we decide to call it a day right there near the Park Interpretive Centre. Camping in the open, quiet desert calls to us, plus the Centre has hot showers and a restaurant. Cost of camp site, $4.65; cost of sleeping under a jet black sky with a million southern stars overhead, priceless.

The little two laners continue to charm us as we wander hither and thither. The neapolitan landscape, with its layers of iron reds, copper green and yellows, lava greys and clay browns is magic. Strokes of vivid green fill the river valleys below, complementing in living green this wonderland of landscape colours.

These roadside shrines are everywhere in La Rioja province. According to popular legend, Deolinda Correa's husband was forcibly recruited around the year 1840, during the Argentine civil wars. Becoming sick, he was then abandoned by the lads. In an attempt to reach her sick husband, Deolinda took her baby child and followed the tracks of the army through the desert. When her supplies ran out, she died. Her body was found days later by gauchos that were driving cattle through, and to their astonishment found the baby still alive, feeding from the deceased woman's "miraculously" ever-full breast.

Gauchos first, later truck drivers, created small altars throughout the country, with images and sculptures of the difunta (deceased). They leave full bottles of water as offerings, "to calm her eternal thirst". Standing in front of this desert homage reminds me how hot I am in my motorcycle clothes and boots. The glistening bottles of offerings encourages me to take a long pull from my Camelback. The water tastes cool and reassuring. The squeeze of lemon I had put in the water helps to quench my sudden thirst as well. Mental note to self: if dying of thirst out here, find a difunta correa shrine.

Travelling through other valleys blessed with water, we pass kilometre after kilometre of olive plantations. Row after row of olive trees march in military straight lines from east to west between the mountain chains. Where bushy olive trees are not, vineyards take their place. As we pass, helmet visors open, we can smell the aerosol spray humidity of irrigated land full of a million green leaves. It is comforting to know life thrives, in what is otherwise desert, so well.

We follow a twisting, hairpin road up a narrow canyon to the Cuesta de Miranda, to a viewpoint 6600 ft asl. As we negotiate the switchbacks, the steep dropoffs below and overhanging rock above us remind us to keep our mind on the road and not on the dramatic scenery. We stop at one-car size pullouts to admire the view and the engineering feat that carved out this part of Ruta Cuarenta (Route 40). Yes, this is the same Ruta 40 that leads one to Ushuaia, only now we're 4000 kms north of el fin del mundo.

At a lovely, spacious and inexpensive cabana ($40/night), we take a few days off. Joyce catches up on her art and diary notes, I tinker (as Mr G would say) with the bikes, and together we wash clothes, spread the maps and guide books out and generally get as many projects going at once as we can.

The big picture needs to be revisited. Our original plan of travelling upstream on the Amazon and exiting South America through Venezuela is looking increasingly risky. Political unrest and crime has risen significantly in Venezuela since 2006. From recent travellers we get sobering stories. If true, the trend makes us uncomfortable: not only are more bad guys preying on travellers but now there are more reports of police corruption as well.

Other factors to consider are, firstly, an unexpected outbreak of dengue fever in Northern Argentina. Two of our destinations, Salta, and further north, Bolivia, are seriously infected. Secondly, the swine flu from Mexico is grabbing CNN headlines. Although we suspect this may be typical baby boomer generation overkill, the world wide attention, justified or not, could close the USA borders to our return in August.

A new plan, based as much as possible on fact and rational decision, is formulated. We decide to turn east for Cordoba. There we can get a visa for Brazil. With our time remaining, we can still check out Uruguay, then see how far north we can get in Brazil before exiting by air.