Brazil 319 - The Ghost Road

Country

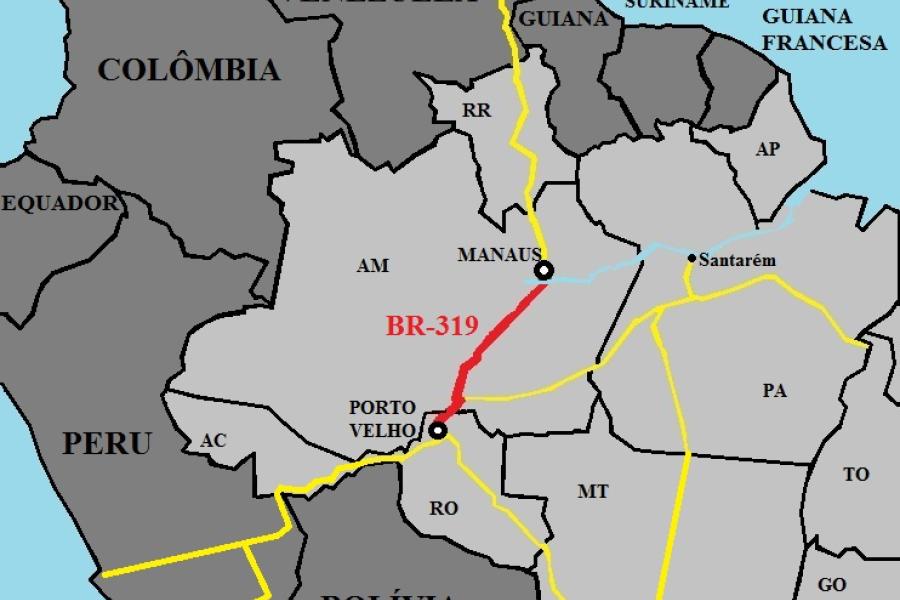

Rewind to 2006-2008, while researching adventure riding, a long dirt road in Brazil appeared on my adventure radar after reading member posts on Horizons Unlimited’s South America forum. Located in the State of Amazonia, BR-319 is a poorly engineered and thinly maintained 655 km long road. Portions are paved, with long stretches that are dirt. By dirt, I mean red clay. Add a little rain and the red clay becomes super slippery, ice skating rink slippery. Add more rain and modest traffic to the mix. What comes out? Horror show stories of travelers struggling in deep mud, up to the axels deep…for days. On a wet day, the clay sticks to tires, making traction a full-on joke. Call me a masochist, but I was intrigued.

In 2008, I had a plan to ride south from the US to the tip of South America. As my departure date got closer, clarity set in. I was biting off more than I could chew. The plan to ride Central and South America was reduced to only riding to Costa Rica and back. South America would wait for another trip.

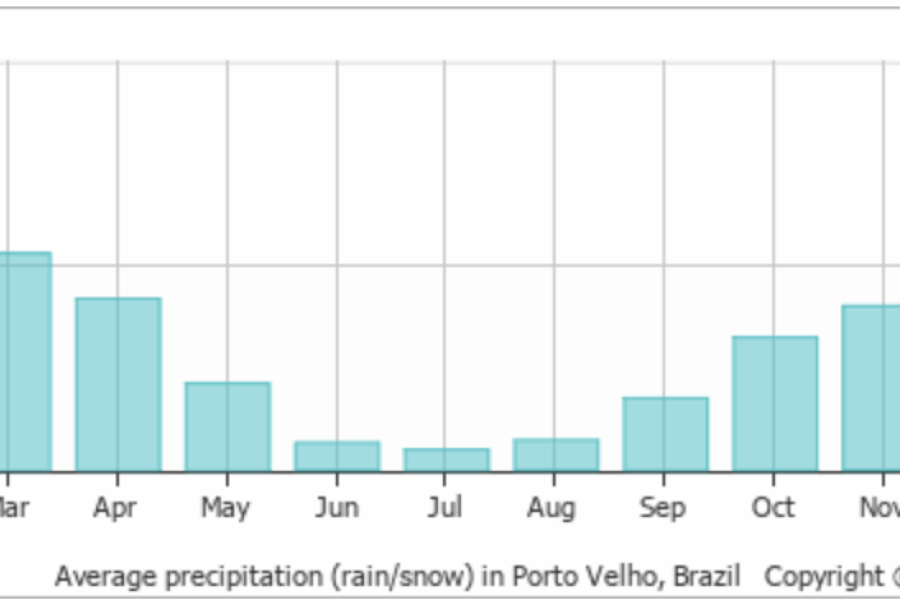

In 2012 a ride from New Jersey to South America started in September, too late in the season to take on BR-319, also known as “The Ghost Road”, by the time I would reach Brazil in November. The annual rainfall would turn a few hundred kilometers of the dirt road into a sea of muddy red clay. Those who arrive after the rains start face two choices: take the ferry on the Madeira River or tell a very long mud story. If I was going to do it, I wasn’t going to take a boat that runs parallel to BR-319.

Why is BR-319 called the Ghost Road? Construction started in the early 70s, and then the jungle and flooding started a battle with human engineering. Nature started to take the land back. The roads washed out, the tarmac crumbled due to poor engineering, and the financially strapped government couldn’t maintain it. At one point they sent the military in to work on the road. Historically lodging is scarce between Humaitá and Manaus. Riders shared stories of wild camping on the loading dock of cell tower facilities. In the decades that followed, loggers, miners, farms, and small settlements appeared along the road. Interestingly, the government established a buffer along the road, cutting trees and vegetation back. With few exceptions now, the rivers have modern or wooden bridges. On my first day on BR-319, I encountered a crew maintaining a wooden bridge. The fight to tame the Ghost Road continues.

Flash forward to 2023, ten years after returning from my first major ride through South America, riding BR-319 was the keystone of the trip schedule. The least amount of rainfall in the Amazon is between June and August. A family reunion in July took precedance, so August became the target to be in western Brazil. The road that has haunted me for over a decade is within reach.

North of the large town of Porto Velho, the last town of any size heading north is Humaitá. The plan, stay in Humaitá for a night, then reach Manaus in two days. On arrival in Humaitá, my priority is to get cash. The ATM at Scotia Bank was my best friend of the day. Next a little ride around town to the western bank of the Madeira River. I spotted a ferry and barges that carry people and cargo up and down the river. Rivers are the highways of the Amazon.

The best practice is to fuel up when first getting into town. In the morning the electricity may be out or the gas stations may have run out. Ask me how I know. Best to not take chances. The Honda runs well on ethanol, in a way. Misunderstanding the fuel specification of the Honda and counter to the concerns of a gas station attendant, I filled the tank with pure ethanol. The bike went about one block before seriously sputtering. Realization slowly dawned on my dim brain, the motorcycle is designed to run well on gasoline with a high percentage of ethanol, not pure ethanol. Too embarrassed to go back to the gas station, I limped the bike along until I found a different gas station. There was a crowd sitting outside watching a soccer game in the combo restaurant/bar/gas station. With my head hanging low I explained the situation to the attendant. Soon a regular was pulled away from the soccer game to help the tourist. After a few minutes of looking at the problem, then he left, only to return with a hose and a container. He was glad to accept the siphoned fuel and wouldn’t take my offer of a beer. Brazilians are the best.

Later that night steak, potatoes, and a salad for dinner. Enormous portions of food arrived including four filet mignons, fries and rice (because everyone loves doubling up on starch!), and a large plate of lettuce, egg, onion, carrot, olive, and tomato salad. Brazilians love big portions. I think when Brazilians go out to nice restaurants they dine as a family and share the platers. Yes, I took some of the food with me and ate it for breakfast.

Dawn breaks on the western Amazon. Loading luggage by 6:00 AM. One hour later I’m looking at the motorcycle travel sticker-covered sign marking the southern end of BR-319, 655 km to Manaus. A short distance later the tarmac ended. Oh boy, the long-anticipated jumping-off point, where the Ghost Road starts.

After an hour, I arrived at the small town of Ser. Realidade. No telling when I would be able to get fuel next, so it’s time to top off the tank. As I pulled back onto BR-319 I didn’t notice a Brazilian rider with a small bag, a bottle of water, and a container of spare gas. The rider, Elismar noticed me, which is expected. With my flashy helmet, riding gear, and luggage, I stuck out.

Stopping to stretch my legs I saw a pair of parrots flying in tandem over my head. Welcome to the Amazon. Some time later I found a spot for lunch on a hill overlooking the road and soon after the rain found me.

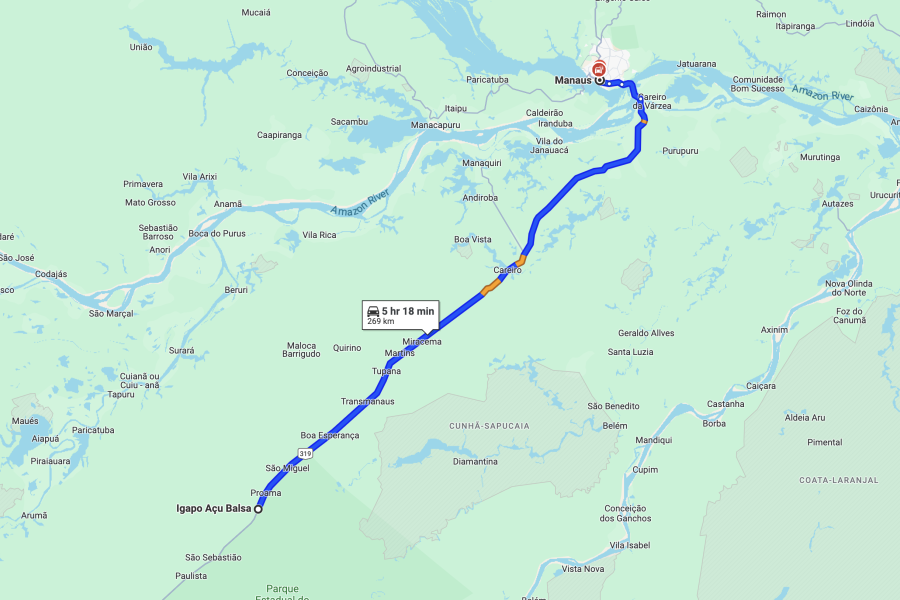

There wasn’t much rain on me, but as I traveled further north it must have rained longer and harder. The surface turned from pack dirt to mud. In no time, riding on red clay soon took all my focus. By mid-afternoon, I passed a few trucks that had slid off the road. An earth mover was pulling one truck back to the center of the road when I came to a line of stopped trucks. Motorcyclists don’t wait in a line of trucks. It is perfectly acceptable for a motorcycle to go to the front of the line. When I got to the front of the line there wasn’t a road worker stopping traffic. What’s the deal? In addition to truckers, there was a lone motorcyclist. Here is where I met the Brazilian rider Elismar. He said the truckers were told a road grader would push mud off the road ahead. Maybe it was wishful thinking. Remember, I had passed several trucks that couldn’t stay on the slippery mud and were in the ditch. So we waited.

I took a picture of a butterfly that landed on the bike. We waited some more. Elismar and I started looking at my front wheel and realized the mud was sticking to the tread at an alarming rate and thickness. The mud would soon stop the wheel from turning. Elismar made a suggestion and I agreed. THe front fender needed to be removed. My toolkit had the right Allen wrench and the removed fender was secured to the bike with an elastic cargo net. Mud would fly everywhere, but I could move forward. We waited for a while longer without road-scrapping progress. Elismar and I decided to press ahead. I’m not a Catholic, but it felt right to cross myself before riding on.

A dozen times the backend of the bike started to slip out from under me. Each time I regained control, with whoops and a deep exhale. The mud never took me down. We rode on into the sunset and beyond. Finding lodging was top of my mind. There wasn’t much time to fret as keeping up with Elismar took all my attention. It was hard to see through a visor building a fine patina of mud. There were huge potholes to contend with in the dark and I was getting tired. Regardless, I was dead set following a Brazilian who has ridden BR-319 five times and I’m not going to lose him!

My GPS told me there was lodging down the road, as the gas gauge informed me the tank was running low. A simple pousada sign appeared in the headlights and our lodging was found. We crossed a footbridge, four planks of wood wide in the dark. A generator hummed in an outbuilding, telling the story of life off the grid. The pousada. Sítio Vale de Baca, offered basic accommodations. It’s not the Ritz, but very welcome. The owner sold us dinner and pointed to a rough shack to shower. After setting up a mosquito net I slept like a baby. In the morning I bought a couple of liters of gas at gun-to-the-head prices. The cost was jacked up, to nearly double the market price. Elismar wasn’t happy with the proprietor and blocked me from buying more. The price of adventure is what I am thinking, but Elismar knew civilization and reasonable gas station prices were down the road.

Morning came and our overnight kits were packed. I removed the security cable locking our bike together and we were off. An hour later we boarded the Agape Açu Balsa (ferry) across Rio Igapo Açu. I have a photo from the ferry, then nothing. Somewhere north of the river, the wheels fell off the wagon, big time.

Telling the story is hard, because the details elude me. I can only reconstruct the day from a very small handful of photos. At some point, I crashed and got a solid concussion. Much of the riding day is gone from my memory. Elismar told me later that I dropped the bike getting off a ferry. The crash might have happened in the morning, after crossing Rio Igapo Açu. If that is where the accident happened, then I lost 5-6 hours of memory riding to Manaus. I have a fleeting memory of looking for gas in a medium-sized town, but it is unclear where. We may have stopped in Careiro for gas. Probably, I am not sure. The worst part is I have no memory, zero memory, of crossing the Amazon from the north end of BR-319 to Manaus. I truly wish I could remember the 45-minute ferry ride across the legendary river.

Elismar had offered to take me to his place in Manaus to wash my muddy clothes. I only remember the last few blocks before we arrived at his apartment. When we arrived, I made a quick physical assessment. My pupils looked right. Balance? Yeah, I’m holding myself up and not wobbling or feeling dizzy. Strength in both hands, no numbness. Fingers and toes can wiggle. Headache, well, yes. Time to call my sister, the doctor.

Communicating what I could remember about the accident and my layman’s workup of my status, she asked an unexpected question. Is my heart racing? I said I didn’t think so and would get back to her. A safe over-the-counter pain reliever was recommended and the promise to call back over the next few days. I had survived. At the time I didn’t want to know and was afraid to ask what it might mean if my heart was racing. I asked the next day. If the impact of a concussion causes the heart to race, a stroke can result. My belief in wearing a helmet was affirmed.

Making it through the mud of BR-319, only to fall getting off a ferry was pure irony. Red clay mud is a nightmare to ride in, yet it didn’t pull me down once. I have ridden on and off many ferries. Probably my experience made me overconfident. It’s the things we are familiar with that can bite the hardest.

Time to attend to a few motorcycle items, see a little of Manaus, figure out a boat to float down the Amazon, and hang out with Elismar and his lovely wife.