Pressing Eastward

Country

In the morning there were several tables of Peruvians getting their morning meal. The breakfast of champions in the US of cereal, eggs, bread of some form or description, and bacon or sausage for the non-veggie crowd is different than the way to start the day in the Andes. The locals were sitting down to soup or as observed a full fried fish. All I wanted, needed desperately, was coffee. While the servers were busy attending to those ahead of me were loading, I felt like a junkie waiting in line for the Methadone clinic to open. Making an in-person plea at the open kitchen didn’t speed the delivery of the coffee. I suspect tea is more popular and pouring a quick cup of Joe isn’t seen as a priority. Then I remembered why on previous trips I carried a jar of instant coffee and would begin my day by unceremoniously mixing caffeine-delivering crystals with powdered milk and cold water. Not pretty, but each “cold brew” cup got me on the road faster. It wouldn’t be until the last month of the trip that I finally remembered to buy instant coffee.

Attempting to climb back up to the ridge road above me was blocked by a road crew spreading a thick layer of leveling soil on the path. Could I go through with my motorcycle? The answer was swift and firm from the worker controlling traffic, No. It appeared that the improvement work was going to take a while. Time to work my way eastward by zigzag through a tangle of small roads on the valley floor. The GPS came to the rescue, identifying the correct path for me to take.

Shortly after rejoining the main road PE-3S, a police checkpoint blocked my progress. In Peru, the police will famously check for the required liability insurance, known as SOAT. Once I failed to leave for an overnight trip without my SOAT card and was stopped at an insurance checkpoint. Fortunately, I had a picture of the insurance card on my phone and the police accepted it. On this particular morning, police were stopping traffic in both directions. One of the officers was blowing a whistle a bit too frequently. After my documents passed review and I was gathering myself up to leave, Officer Whistle blew his micro authority device yet again, this time hitting a nerve in my tightly wound system. To offset the excessive shrill, I blew a whistle that was attached to my key lanyard a few times. Officer Whistle gave me dirty looks and his fellow officers all had wry smiles on their faces. Not the first time I have had a little fun and broken up the randomness of authority.

By midday, I had passed through Ayacucho and soon climbed to a higher elevation. Clouds moved in and the temperature dropped. As drizzle turned to snow flurries I put on warmer clothes. A few kilometers down the road, my heart went out to a man and woman on a motorcycle wearing t-shirts. They must be cold! The winter gloves and heated vest that I brought for use in Patagonia were deep at the bottom layer of the duffle bag. Press on, it will get better I said to myself. I rode through a mix of light rain and snow that did not stick to the road. After an eternity, the road twisted down and the mountain ridge to a lower elevation and warmer temperatures.

Chilled to the bone I stopped in Ocros, the first village hoping for lodging and warmth. Ocros is roughly five blocks deep and three blocks wide. The one or two decrepit buildings that may have once supported lodging for travelers had no sign of life. There wasn’t a local Peruvian tourism office and Google Maps wasn’t fruitful. What to do when you can’t find a place to stay? The answer, go to the police station, of course. On a trip years ago I arrived in Rondo, Peru, as the sidewalk was being rolled up for the night. It wasn’t hard to find the police station then and I found the station in Ocros without trying hard. A helpful officer walked the two blocks to an unmarked hostel and the owner quickly unlocked the door. The hostel was very basic and didn’t have parking for the motorcycle, so I went back to the police station and asked if I could leave the motorcycle overnight in their secure parking compound.

When asking for such a favor, it’s important to say you’re asking for one night. Years ago in Guyana and French Guiana, I asked police if they knew where I could “camp for one night.” Both times I was offered a place to set up my tent within their fenced parameter. There is a difference between saying for one night and camping. The phrase “camp” can mean a site where workers to stay indefinitely.

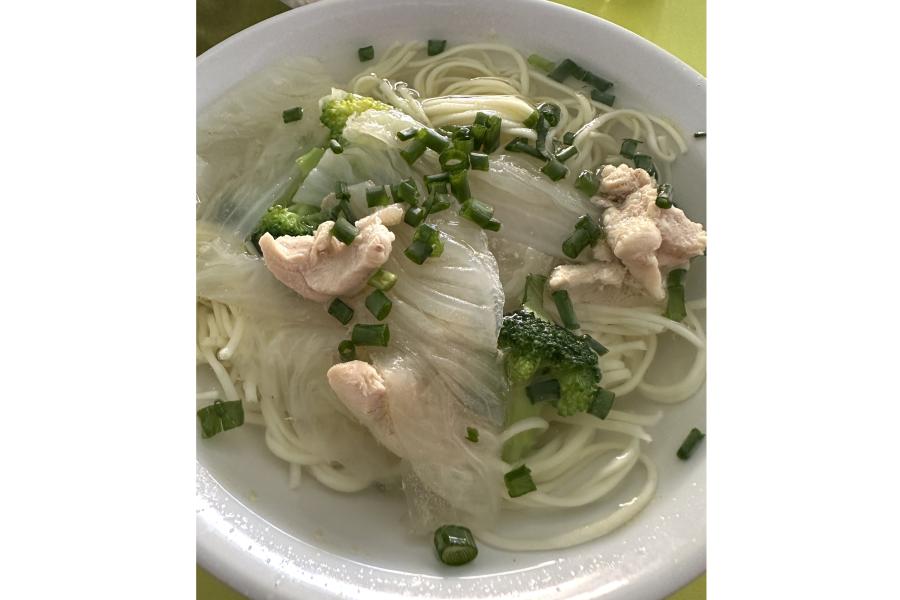

The following day was mostly riding, with one exception. Reaching Andahuaylas at lunchtime Chifa came to mind. Over a bowl of wonton soup, I struck up a conversation with an interesting-looking guy who was picking up food. As we chatted, I learned he was from Brazil and travels around South America selling jewelry he designs. Would I like to go to the central square and see his pieces? I begged off as I wanted to reach Cusco that day and asked if he would mind posing for a portrait. I would meet the jeweler Calu Vaz Barbosa again, five days and 819 kilometers later in Puerto Maldonado, Peru. What are the chances?

As the sun got lower I decided to stop in Curahuasi. Before leaving on the trip I downloaded points of interest by country from the iOverlander website and loaded them into my GPS. The reviews suggested the Panamericano hospedaje. I was set for the night.

Travel for long enough and you’ll see crazy stuff being transported. Mining equipment usually takes top billing. I have seen enormous industrial parts that I could not cipher their purpose. The object de jure was on the bed of a pickup truck. It’s only weird because its purpose is unknown to me. I suspect the red machine was used to process corn or other crops.