Rustus McGrabhandle

No, Ive never heard of him, and no relation either.

I was pondering the question of carrying water on the journey in Africa. The ideal method would be a 5-gallon earthenware pitcher supported comfortably on the top of the head, with a large square of colourful ethnic fabric twirled and twisted into a circular pad to cushion it. Such an elegant and traditional way of carrying lifes basic necessity, and used an awful lot in large parts of the world. It would be just fine, except the crash helmet always seems to get in the way.So I was looking around for whats available when your head isnt, and came across the Kriega and Ortleib catalogues.

An Ortleib 10 litre water bag fits neatly into a Kriega US10 tail pack, which in turn fits on the top of my NonFango topbox using the straps that come with the US10, plus a reinforcing strap over the top.

10 litres of water. Dont yet know if itll stay there on an African dirt road.

Weve just returned from a camping weekend on the south coast trying out this arrangement, just a short trip on tarmac, and it all worked OK.

Anyway, I saw the Kriega Haul Loop (which is a front grab-handle) on a website and remembered that the Yamaha Serow has always come with a front grab handle as standard, but not the TTR.

I think its a pretty useful device. In the Kriega publicity theres a dramatic illustration of one being used in anger

which brought back memories of a major expedition I undertook in the early 1970s.

This expedition involved the organisation of multiple modes of transport, all needing to connect punctually to ensure that our adventurous group arrived at ports of departure in time for our pre-arranged sea-crossings. It culminated in an exhilarating and punishing ride right to the very top of the highest mountain of the country of our destination. And a front grab handle, pretty well unknown in those days, would have been worth its weight in gold on that climb.

It was 1971, and we four members of the Wimbledon and District MCC departed Fulham for Euston. Fulham was affectionately known as 'London SW Zinc' back then. You could get anything you wanted made for your motorbike there, always in zinc. Completely rustproof.

At Euston station we rode our 1950s and 60s trail bikes straight into the guards van of the 08:16 London to Liverpool train. In those days such things were possible in Britain; parking your motorbike in the guards van of a convenient train going your way to save you the trouble of actually riding there. (Except Sundays on this occasion, the day of our return to London. Engineering Work has always been a wonderful feature of the railways, and forced our little expedition to rent a van for the trip back home).

Arriving off the train in Liverpool we hit the road again, all the way to the sea port for the ferry to the Isle of Man, and that years International Six Days Trial. By the time we arrived at our hotel in Douglas wed clocked up at least eight and a half miles for the whole journey.

The ISDT of course is a six-day event, but some days we skipped spectating and did our own thing, and on this particular day we decided it would be pretty good fun to ride off-road all the way to the top of Snaefell, the highest mountain on the island. Indeed, there is no road to the top of Snaefell, only a light mountain railway line that circles around its steep slopes. And a footpath. Wed heard that riding up there wasnt a simple task, even that some attempts end in dismal failure. But its all grass as far as we could see and looked fairly smooth so we thought it would be no problem at all. And anyway, we had magnificent, or magnificently old, British Greeves trial bikes! That had done eight and a half miles all the way from London to Douglas!

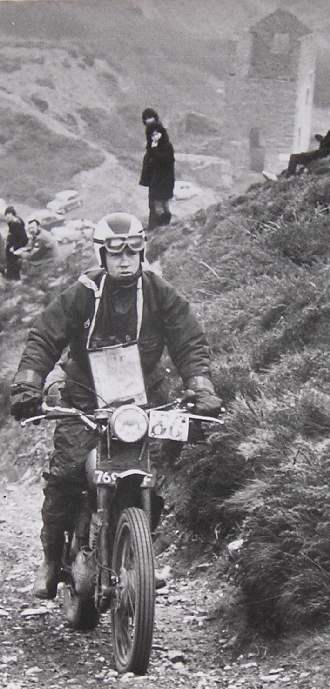

My Greeves, near the end of a Lands End Trial in the late 60s.

7690 PF, where are you??

So we set off from somewhere near Laxey, on a straightforward track that took us up to The Bungalow, which is the highest point that the public tarmac road reaches. The mountain train to the top also stops here. We crossed the road and the railway line and continued onwards and upwards, the actual summit still out of sight. After a quarter mile or so, heading straight for where we thought the summit would be, two things happened.

The slopes just below the summit came into view. Or at least, the dense clouds that covered those slopes. We werent worried about that, wed seen a mountain train leave The Bungalow heading for the top so we knew that the tea house up there would be open, warm and welcoming.

Then, the nice tussocky grass that was pretty wet and bumpy but otherwise gave enough grip to make progress up the slopes, suddenly became floating grass. It was floating on huge peat bogs. In pretty short order the sump of my bike was skimming the bog, then the wheel axles disappeared and forward progress came to a halt.

The bike was upright with me on it, in gear, engine running, rear wheel invisibly turning, and stationary. Boots full of water.

I looked around to see what the others were doing and noticed that a little way ahead the fairly steep slopes became incredibly steep slopes, and the rest of our little group were in the same difficulties as me. Except Jeff.

Jeff was an expert competition trials rider, on some fancy Spanish trials bike, but more importantly than all that was about six foot eight inches tall. And had hardly noticed the deep boggy mud wed hit until he realised he was riding on his own.

My memory of that is seeing Jeff walking down towards me as I realised that I couldnt get off my bike towards the left as the ground rose too steeply on that side and my bike and I had sunk too far into the bog. So I let go the bike and slid off to the lower ground on the right, whereupon I sunk into the mud until my eyes were at the level of the petrol cap.

Get on it and go! hollered Jeff. I wondered if that was a joke. He approached some more, started sinking into the same bog as me, realised it was no joke and retreated promptly.

Youll have to push!

Another joke I thought. I could hardly reach the handlebars, they were up above my head, and any pushing would only push the bike further over into the bog.

Then another difficulty overcame us (except Jeff, that is). As we looked around at each other, in various states of submersion, engines still running producing huge steam clouds that floated off towards the real clouds, we realised how funny our situation was and could do nothing but burst into gales of disabling laughter.

Jeff stood and watched, growing impatient, frowning. He was doing fine, his bike still on the ground and not in it, and he just wanted to reach the mountain-top for tea. But he couldnt get any nearer to us without sinking into the mud himself. So he made himself useful, in true Captain Mainwaring style, by shouting orders at us in a vain attempt to stop the laughing and get to his cup of tea.

Pull on the front wheel!

All that happened was the wheel turned.

Pull on the handlebars!

The bike fell further over.

We ignored him and somehow organised ourselves to pull one bike out at a time. Here another serious danger arose.

To make any progress we had to get our legs and feet out of the bog and up to surface level. And importantly, with boots still attached.

That was difficult. As well as pulling the boots to the surface, the weight of the water inside each one also had to be pulled up, and Jeff had no advice to help us there. All we knew was that if anyones foot became detached from boot whilst still two foot down in the bog, the boot would be lost forever, leading to a pretty interesting ride back to the tarmac road and the hotel in Douglas.

(McCrankpin has to confess here, that in the same Isle of Man the previous year for the TT, somehow or other the tarmac road came between his left foot and the boot it was in, turning the boot into leather scraps. And at the same time his bike came between his right foot and the boot it was in, transforming that into shreds as well. He didnt want to end up boot-less on the Manx roads two years running, thank you very much!)

So it was here that the value of a front grab-handle became clearly apparent. But I never saw one for sale in those days, not even a zinc one in Fulham.

Im not too sure how we managed to get out of that bog, but I do remember that the only thing to pull on was the front wheel, with the spokes seriously in the way, and most pulling only resulted in the wheel turning. Heres a photo taken down near Laxey, not of us, but gives an idea of our situation. Except the slope was much much steeper. (Any photography would have been impossible even if wed had cameras, and I dont think anyone did).

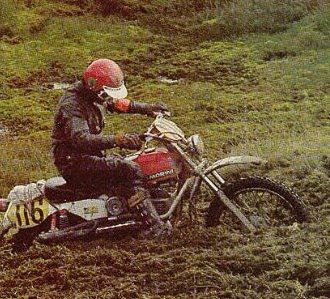

In the absence of grab handles, other methods are sometimes necessary:

We resorted to using four pairs of hands and feet per bike, and got them all onto firmer ground and up to the summit tea house.

Jeff had no sympathy whatsoever.

Those bogs were dead easy to see! You must all have had your eyes closed!

Maybe we did. With his guidance we had continued to the top with no further sinkage nor loss of boots.

When you get bogged down a bit, just use your feet and throttle and get some weight off of the front wheel!

We stood him up, we all stood next to him in line, and got him to admit that the tallest of us was a foot shorter than him, and would he shut up please? Last one back to Laxey buys the beers

..

So with those memories prompted by the Kriega advert, McCrankpin decided it would tempt fate too much to depart without one of their front grab handles fitted.

The camping weekend was a straightforward affair, and didnt test any of our gear to the standards needed for Africa. But helped with familiarisation.

We also had some success with a pair of ex-military gas-mask bags that Caroline bought for tank panniers for her Serow. After she bought them we realised that neither the original Serow tank, nor the Raid tank, were of a shape or size that would take any sort of pannier. But I remembered the pictures of Lois Pryces Serow in her book, so at the campsite we tried hanging the gas-mask bags either side of the headlamp.

Bingo! Theres something about that Serow headlamp and front mudguard arrangement that makes a pair of military bags fit precisely eitherside of it, tucked neatly underneath the indicators, with the few yards of straps that the bags come with holding everything nice and securely. And front grabhandle still accessible.

Caroline and Beau arriving back home from the campsite, panniers still in place, and full of heavy books that Caroline happened to have with her for the weekend. (Dont ask!)