The Trans-Kalahari Highway

I'm reviewing the situation.

It'll be decision time again in Windhoek (Namibia), on which route to take thereafter.

Firstly, I stayed a few days longer in Ghanzi (Botswana). It's a cultural centre of the San bushman tribes. I read a little about their situation in the Ghanzi public library.

Travelling along the roads east to west in this part of Central Botswana it's noticeable that there are numerous large billboard signs on the outskirts of towns, urging people to "Know when to say No!" With an additional slogan about responsible drinking, in English and the Botswanan language.

On arrival in Ghanzi I saw a large hotel sign above a bar area inside a parking compound. So I rode in, to find quite a lot of people drinking merrily, outside in the compound and in the bar. I couldn't find any hotel reception and the customers were keen to help me, but it took a while for them to string the words together to explain that the sign for the hotel above the bar was only an advert, the actual hotel was two buildings further along. So I don't know if there's an alcohol problem around here or not, as I never saw any other indications that there might be.

In the library I learned that the San people don't actually refer to themselves by that name, it's a label that's come to be used by western publications. Up-market guide books and holiday brochures for instance, refer to the San people in advertising their luxury safari package holidays in Botswana, and particularly in the Okavango Delta. In some communities the word 'San' is considered derogatory.

The people themselves use names that refer to the language group that they come from, there being about eight different languages in use, although all generally related. These names were deemed too complicated to use in adverts for posh trips to indigenous villages.

Also, on average, one western film crew per month descends on the villages on the north-western edge of the Delta, to film advertising material, glossy magazine features or TV travelogue footage. The usual set-piece demand is for the villagers to dress up in their tribal costumes (which they do anyway), and walk across the salt pans for the cameras, armed with ceremonial spears - which they never normally do.

"Why would we do that, there's nothing out there on the pans. We don't live near them and they're empty except for tourists on quad bikes!"

Quite!

But the enigmatic image is of a 'San Bushman' walking across a salt pan in his tribal garb. And like everyone else, they need to earn the money that makes this world go round so they accept the film companies' fees.

I also learned a little more about Cecil Rhodes, in particular his dealings in what is now Botswana. He was more of a rogue than I thought he was, and that was quite a lot of a rogue.

In the late 1800s a group of Botswanan chiefs travelled to London to lobby the then government. They accepted the idea of their territories being protected by the British against incursions by other enthusiastic European colonising countries, but had two demands for the government.

That the land taken from them by Rhodes in fraudulent deals be returned, and for the British to ban all import and carriage of alcohol into their territories. Rhodes tried to stop them in Cape Town on their way to England but failed.

The chiefs' two demands also failed, the British view being, more or less, 'a deal's a deal'.

(Rhodes did later lose the land he took from the Botswanan people, as punishment for launching his abortive 'Jameson Raid' from Botswana against the Transvaal. But the land was then appropriated by the British government rather than being returned to the tribes).

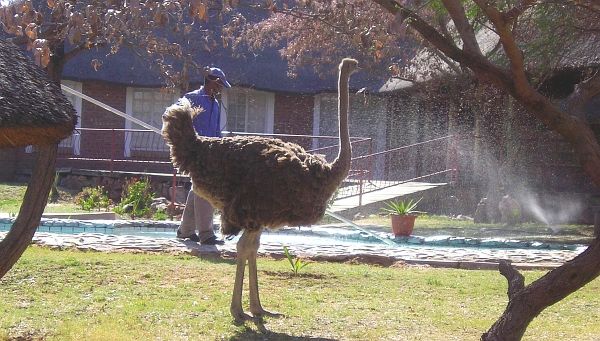

After a few more days in Ghanzi, and marking the one-year point of this journey, I departed for Namibia and Gobabis. But took this photo first of some local widlife that seemed to spend time around the hotel building but left the campsite alone, I'm glad to say.

Back on the Trans-Kalahari Highway,

the road continued as featureless as before.

Right up to the Namibian border. Which was the quickest border-crossing so far, I think. And the emptiest. Only me and one truck, carrying brand new cars into Namibia. (But a big tour group going the other way).

Then the road continued, even dryer and bleaker. And maybe even straighter.

And then this, about halfway to Windhoek:

It's like that restaurant I mentioned once before, called 'Three Chairs Missing'.

I'll call this place 'One Letter Missing'.

And things became a little more interesting. Trees returned.

And distant mountains.

And a distant horizon at last.

And I began to review the situation of the next bit of my journey.

I stopped in Gobabis that night, within easy distance of Windhoek and the next major crossroads.

The last few day's travelling had brought about quite a change. In the scenery, the atmosphere of the towns, in the people, in everything really. And memories of what many other travellers had told me over previous months began to queue up to be reviewed.

"Isn't it funny, how the more prosperous people become, the less happy they are."

"The further south you go, the more expensive it becomes."

"You have to remember, the people who say how wonderful the south-west coast is, the Namibian deserts and sand dunes - for a lot of them that's the only bit of Africa they've seen. They've never been to Ethiopia, Sudan, western Tanzania, the Sahara."

And so it goes on. And it seems to be true.

Just recently I've heard from Sabine and Bodo who accompanied us on that other highway, the Trans East-African Highway of northern Kenya. (Unlike that one, this Kalahari version is all smooth tarmac, neat verges, straight, and so boring.)

They are ahead of me, and have had their Mercedes truck broken into and cameras stolen, inside a fenced and security-guarded campsite on the Namibian coast.

And there was Pedro, an American who has lived in Johannesburg for many years but is now on an open-ended journey going generally northwards to see the rest of Africa. I met him in Gweta on my way to Maun and we exchanged lots of information.

"Be careful in Namibia and South Africa," he warned. "Lots of thefts are inside jobs, arranged inside guarded hotels and lodges. And Windhoek may not be a good place to stay in, there are reports of travellers witnessing violence on the streets."

A couple of days later I happened to read Sabine's blog: "We have our cameras returned, the police seemed to know where to find them being sold on the streets, but no one is arrested. And as I write this, a man is running down the street being chased by another wielding a machette. And a car is involved as well."

In Mikumi, southern Tanzania, I met Max, a Kenyan documentary film maker returning by road from the World Cup. He had been making a documentary about the effects of the football competition on the lives of ordinary black South Africans in and around Cape Town.

We talked quite a bit, and he said, "You may not like it when you reach South Africa and Cape Town after travelling all down the east coast."

"There, society is still white-dominated. In a restaurant everyone will be white, the only black people will be doing the cleaning and washing-up. Despite all that Nelson Mandela did, things haven't changed very much. I've been making a film about that and who the World Cup really benefitted."

He had been a journalist on a national Kenyan newspaper but went freelance with a camera after he found his stories were never published as he wrote them. "Everything is edited so that it falls in line with the western view of Africa."

He had two Italians with him who were independent film-makers and helping to get his documentary published.

"No one in the established film industry will touch this stuff because of what I've filmed, but these two may be able to get it out to the public."

So, things may be different ahead.

Certainly, over the last week, the number of 'large' people in the streets has gone from zero to a noticeable amount, and the number of morose and sullen faces, ditto. The cheery welcomes and greetings and hospitality aren't so cheery now.

There's also the paperwork.

My customs Carnet for H.M. The Bike expires at the end of October. Renewal shouldn't cost an arm and a leg, like the first edition, but will be well into three figures. And being in the Southern Africa Customs Union means I have to deal not only with the RAC back home but also with the South African version of the RAC, with papers, forms and phone calls passing between all three of us. The courier charges for sending all those papers around will probably be three figures as well, and I have to have a postal address for a while. So is it worth extending it? To stay longer in an area I might not like?

So, a decision needs to be made in Windhoek.

I can either turn left, to the south and the South African border, missing a lot of the Atlantic Coast. But arriving in Cape Town in time to ship the bike back home before the end of October.

Or, turn right, to the north, the Skeleton Coast, the Namib Desert, the Swakop river, and a few hundred more miles and more time.

Well, for a few moments I thought on that in Gobabis, but decided that I'd decide what to do once I'm on the road to Windhoek the next day. See how things felt, how the bike was going, what the weather was like.

So I set off west the following morning, thinking I don't really need to decide, left or right, until I've been through Windhoek on the way to its Western Bypass on the far side. And really, I can even wait until I approach the bypass junction, so

......... I think I'd better think it out again.........

when it's time to press the L-R indicator switch.