Bolivia

The border crossing from Peru to Bolivia at Copacabana was the most relaxed and friendly experienced so far on this trip. There was no one else crossing into Bolivia so I got the undivided attention of the staff. The only downside was being charged $5 by the Bolivian policeman who had to check that the paperwork just issued by immigration and customs was in order. Im 99% certain the payment was unnecessary and illegal but at least the policeman was cheerfully welcoming me into his country as he robbed me.

My Opportunity To Enrich A Bolivian Policeman

Copacabana has a perfect setting beside Lake Titicaca and an awesomely long and steep climb to a mirador (viewpoint) with great views of the harbour, well worth the effort of the climb although it did feel as though my heart was trying to pound its way out of my chest by the time I got to the top. Another of those occasions where Im left wondering whether the thumping heart and panting for more air is due to the altitude or old age.

Lake Titicaca From The Copacabana Mirador (Viewpoint)

Before I left the UK to start this trip in 2009 I had done some preliminary research into Bolivia. The country got a lot of rain, although as always in the Andes, mainly on the eastern, Amazon side of the mountains. The roads were in a poorer state than neighbouring countries and the Bolivians were prone to blocking roads as a form of protest. I definitely wanted to visit Bolivia and if the roads proved too bad I would park the bike and take four-wheel drive tours. My initial tactic, should I be unfortunate enough to come across a demonstration blocking the road was to simply avoid a confrontation, turn around and find an alternative route. This plan seemed to make sense in the UK but in Guatemala I had encountered a demonstrators roadblock and the best alternative route was going to take around three days to get to a town four hours away by the blocked direct route.

June is the driest but coldest month in Bolivia and I had paced my trip to arrive in June thinking that the rain and the washed out roads are harder to deal with than the cold. The plan worked out, I only had one day of light drizzle, daytime temperatures were ok but it was decidedly cold in the evenings and through the night.

Copacabana Sunset Over Lake Titicaca

You have to use a ferry to cross Lake Titicaca to get from Copacabana and onto the road that leads to the capital city, La Paz. The ferry was a slow primitive affair with an open stern. I had to squeeze onto the end behind a truck and a small bus which left me close to the open end on loose planks of timber. The main concern was unloading backwards but fortunately it was downhill and it wasnt too difficult with the help of the ferry driver.

Ferry Across Lake Titicaca

Travellers leaving Bolivia had told us of fuel shortages caused by demonstrators roadblocks stopping supplies being distributed around the country. Also, since the start of 2012 any non Bolivian registered vehicle has to pay almost three times the price as locals for fuel. Sometimes foreigners were refused fuel as the station had either run out of the necessary forms that needed completed or the staff couldnt be bothered to fill them in. I was keeping an eye out for fuel stations on the way to La Paz and most had the pumps covered over which was a bit worrying.

I entered La Paz at El Alto which has an elevation of 4150 metres then plunged down to the city centre at 3500 metres squeezing past fleets of local buses triple parked to pick up passengers. At a complicated road junction with what looked like a roundabout there was a total gridlock of traffic, mainly small buses trying to go around the roundabout in both directions.

La Paz In The Valley Below From El Alto (Photo By Fletch)

The Death Road

I met up with Nick again who I had first seen in Cusco and another rider Fletch in La Paz and we decided to do the infamous Death Road together. The Death Road used to be the main road connecting Coroico to La Paz. It has the typical mountain road features of long drops on one side of the road and a cliff face on the other. Over a total distance of around sixty five kilometres the road rises to a maximum altitude of 4650 metres at La Cumbre Pass then plummets all the way down to 1200 metres. The road was unpaved, narrow and would have been chewed up by all the traffic when it was the main road. Between 100 and 200 people a year died on the road before the Government widened and paved part of it and built a paved bypass around the most dangerous section. Most fatalities occurred when two vehicles came towards each other and had to attempt to squeeze past resulting in one of the vehicles going off the edge of the road and plunging down the mountainside. The biggest single accident was on the 24th July 1983 when a bus careered into the canyon killing over 100 passengers.

The Death Road (Photo By Fletch)

The remaining narrow dirt road section of the Death Road has some impressively steep drop offs down to the valley bottom but the surface is well maintained and since the bypass has been completed the vast majority of users are tourists, most of whom are on mountain bikes. You can ride the road in either direction but most people go downhill away from La Paz on the dirt road then return uphill on the paved bypass. On the day we did it we didnt come across any traffic coming in the opposite direction. Unfortunately we had a fair bit of cloud, mist and drizzle obscuring the view but it was well worth doing and it was a long way short of being the most dangerous road I have ridden on this trip.

The Death Road (Photo By Nick)

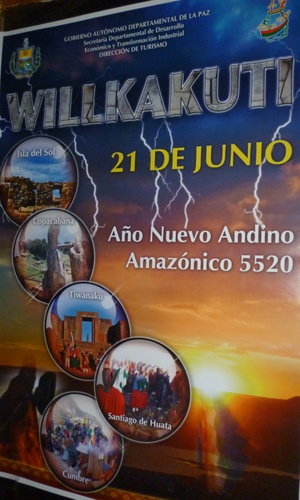

Nick, Fletch and I left La Paz on June 21st, the Andean New Year which; like the ancient Britons pagan mid winter festival celebrates the winter solstice. By the Aymara calendar it was the start of year 5520. There were various indigenous celebrations going on which we missed but we figured that the roads would be quieter during the holiday.

Happy Andean New Year

There are two routes from La Paz to Sucre. The road via Potosi was reported from numerous sources as being paved the whole way. The few scanty and older reports we found on the alternative, Highway Six suggested it was a dirt road with numerous roadworks and possible diversions. I had made my mind up to stick to the paved road rather than risk hundreds of kilometres of unpaved road with no recent information on its condition when we discovered an internet forum post less than a month old saying the road was now paved the whole way. Great news. I intended to return north on the Potosi - La Paz road so I could head to Sucre on a different road making a circular trip. We assumed; as earlier reports had mentioned roadworks that these were to pave the road and that they were now complete.

Nick, Fletch and I set off for Oruro having topped up our fuel tanks before setting off from La Paz in case there were problems getting fuel later on, something we did throughout our travels in Bolivia. I was surprised that the fuel consumption on my BMW F650GS was almost half that of Nicks on a Suzuki DR650 and Fletchs on a Kawasaki KLR 650. However climbing up the steep road from central La Paz they were pulling away from me and I had the throttle wide open so they had more power.

The Paved Section Of The Oruro - Sucre Road (Photo By Nick)

We had to pass through Caracollo on the way to Oruro. The Pan Americana Highway had been blocked by a demonstration here for four or five days but we hadnt been able to get a recent update so didnt know if it was still in place. Although non of our maps showed an alternative route there was rumoured to be one so we planned on dealing with the situation when we got there. As it turned out there was no sign of the demonstration and we had an uninterrupted journey on paved roads to Oruro.

The following day saw us setting off after breakfast in the cold early morning and after an hour or so we were turning off the Pan Americana onto Highway Six, the direct road to Sucre. At a small mining town we stuck to what appeared to be the main road but ended up at a barrier at the entrance to the mine. Our road was on the other side of the river but after a chat with the mine security guards they allowed us to ride onto the mine property and cross the river on a rickety railway bridge. One of the steel plates bent alarmingly as the others rode over it but if it carried their weight I wasnt unduly worried, I was more concerned with getting a very wide bike over a very narrow footpath at the side of the railway track.

After the excitement of crossing the railway bridge and getting back onto Highway Six it changed to a dirt road although the surface was ok most of the time our speed dropped, particularly mine. The real problems started when we arrived at another road barrier. The road was closed until 6pm for roadworks. We could wait over four hours by which time it would be getting dark or take the detour. As it turned out it would have been quicker and easier to camp at the barrier and continue on Highway Six the following morning but at the time there wasnt any discussion we headed off onto the detour without knowing how long it was or what the road was like. It turned out to be a rough, narrow track which I found particularly tiring. We pulled into a village around 5pm which judging by the crowd that quickly assembled wasnt used to strange visitors on large motorcycles. Nick and Fletch went off to look for supplies and to see if there was any accommodation available while I kept an eye on the bikes. There was no possibility of getting to Sucre that day. The village didnt have anywhere for us to stay so we headed back onto the Alto Plano to find a campsite.

Preparing For A Chilly Night On The Alto Plano (Photo By Fletch)

We found a scenic spot off the road and out of the worst of the wind, quickly got the tents up and rustled up some food with the scant supplies we had between us then climbed into our tents before it got too cold. Being slower than Nick and Fletch I set off first the following morning confident that it wouldnt take long for them to catch up. There was a rough, fairly deep river crossing that I got through but had to put a foot down; getting a boot full of icy water in the process. Knowing the others wouldnt be far behind I waited to get photos of them at the river crossing, the first of several we had to tackle that day.

Fletch Splashing Through One Of The Rivers

Nick Splashing Through The Same River

As Befits My Age; I Take A More Sedate Approach! (Photo By Nick)

We rejoined Highway Six at the village of Pocoata where Fletch went off in search of fuel while Nick and I stocked up on food supplies and water then we continued on the dirt road with occasional short detours onto tracks with a layer of slippery bulldust. These detours were due to the re-grading of the dirt road, we never saw any indication that the road was being paved. As we thought we were getting close to our destination of Sucre there was another longer detour, thirty or forty kilometres due to a landslide blocking the road. Unbeknown to me Nick and Fletch, running ahead of me had stuck to the main road hoping to squeeze through but found the road completely blocked and had to double back onto the detour. The detour wound its way up and down some steep hills with tight bends and there was more of the slippery, talcum powder like bulldust. I was exhausted again; riding the bike further, on rougher roads than I wanted to. I dont mind short stretches of rough road but I dont have the stamina to tackle hours, or in this case two full days of rough stuff. On a steep, tight downhill bend I dropped the bike at low speed in the bulldust. I couldnt pick the fully laden bike up from its position sitting neatly on the pannier and had just started taking the luggage off to lighten the bike when Nick and Fletch unexpectedly arrived. I thought they were ahead of me but I had taken the lead while they went down the main road to the landslide and had to double back. The three of us quickly got my bike the right way up. I was too tired to ride much further and intended to stop at the first hotel or area I could put a tent up although as it turned out there wasnt a hotel or campsite along the road and we eventually pulled into Sucre in the early evening.

Ooops!

I have been on longer, rougher roads than I wanted to be on before on this trip and fully expect I will be again but this has always been because of the lack of information on the condition of the road. I always try and research my route and pick my battles on which roads I want to tackle. This was the first and I hope only time I ended up on a road due to blatant misinformation. I cant begin to imagine why anyone would comment on a road they clearly know nothing about. Until now I assumed that anyone posting on a forum had recent, first hand knowledge on the subject and happily took their advice but sadly I will think twice before doing so in the future. Nick and Fletch would have chosen the Highway Six route even if they had had accurate information beforehand and enjoyed the challenge as Im sure I would have done twenty years ago.

The Sucre hostel we stayed in had a number of stone steps leading up into the reception area and through into a courtyard where we were to park the bikes. Nick and Fletch attacked the steps with gusto and Nick in particular had the front wheel well into the air. Following their lead I took the steps at speed but with my lower ground clearance almost came to a standstill as I removed a chunk of stone from the top step with my sump guard. The staff looked concerned as they examined the damage to the step whilst I was surreptitiously inspecting the sump guard. To make amends and make getting out of the hotel easier I found a timber yard and bought some lengths of wood to form a ramp which hopefully will be kept for future motorcyclists.

Our Sucre Hotel

Sucre was a nice place to hang out, in my case while my stiff and sore muscles eased and relaxed themselves. Nick and Fletch went off to do the Che Guevara loop to La Higuera, the village where Che Guevara was capture in a gun battle then executed. I wanted to visit the village myself but needed more R&R time and by waiting until Nick and Fletch returned I could get an up to date account of the road. When they did get back their information would probably have frightened me off tackling the route but whilst they were away I got an email from my Australian nephew, Jamie who I was due to meet in northern Chile. He was backpacking from Santiago to Cusco and Machu Piccu and wanted to meet up earlier than we had originally planned so I decided to skip my homage to Che and make sure I got to Iquique for our brought forward reunion. Jamie was about ten years old the last time I saw him but if he is backpacking around South America I assume he is a lot older than that now.

I headed out to Potosi on a good paved road where I was staying one night, leaving most of my luggage to travel light to Uyuni to see the salt flats then make my way back to Potosi, pick up my luggage and head to Chile via the cowardly paved route through Oruro, Patacamaya and the Chungara Tambo Quemado Pass to Arica.

There are numerous older reports on the internet about the challenging dirt road between Potosi and Uyuni but I had met a South African rider who had travelled on it recently and said it was now all newly paved apart from around twenty kilometres where there was a detour for roadworks. A short distance out of Potosi I stopped at the memorial to Kevin Irvine, a Scottish Canadian motorcyclist who was sadly killed earlier this year. I never met Kevin personally but know several riders who did know him. It was a sombre reminder of what can happen to any of us.

Kevin's Memorial

The road was laid with beautifully smooth new tarmac, so new that along most of its length crews of workers were still painting the edge and centre lines protected by nothing more than a man waving a red flag. The detour was at the Uyuni end of the road but most of the unopened section was paved and looked like it will be open very soon. No doubt this will be good news for some and bad news for others.

Uyuni Train Cemetery

I liked Uyuni although it was freakishly cold at night. I stumbled across the train cemetery on my first day as I attempted to walk to the edge of the Salar (salt flats). The salt flats are deceptively much further away than they look and never appeared to get any closer despite walking for a couple of hours.

Uyuni Train Cemetery

Graffiti Reads - "You Need An Experienced Mechanic"!

The following day I rode to the edge of the salt flats and could certainly appreciate why riders head off to cross them taking around three days to get to San Pedro de Atacama in Chile.

The Bolivian Salt Flats (Salar)

On the Pan Americana Highway between Potosi and Oruro I came across my first and only Bolivian road blocked by demonstrators. A line of parked vehicles was the first indication; then the deserted road ahead was strewn with truck loads of rocks. I pulled up at the front of the queue where someone told me the next six kilometres of road were blocked. There was no sign of any demonstrators and I decided to walk further ahead to see what was going on. Over the brow of a hill I saw a group of fifty to sixty people with some flags planted in the middle of the road. I asked one man if I would be allowed to pass on a motorcycle and was redirected to the group leader who after asking a few questions agreed to let me ride through. When I returned to the demonstrators on the bike half an hour later a lady in a bowler hat deliberately walked in front of me to place a stick on the road between two rocks to block the gap I was riding towards. It was easy enough to find another gap but I made a point of waving and shouting my thanks to the guy who had given me permission to cross to let the other demonstrators know I was allowed to cross. There were several other groups of demonstrators scattered along several kilometres of road and I had to repeat my plea to be allowed to continue. I was worried that one group might refuse and I would end up stuck in the middle which nearly happened to me in similar circumstances in Guatemala. Whilst I was slowly weaving through all the stones hundreds of bus passengers were carrying their luggage across the area sealed off by the demonstration. The bus companies had buses at either end but passengers had to disembark and carry their bags to the buses waiting on the opposite side of the protesters.

In the end I didnt have problems getting fuel in Bolivia although I did fill up more frequently just in case. The forms at the filling stations were rarely completed, On one occasion the attendant forgot to charge the foreigner surcharge on fuel and I forgot to remind him. The country seems to be tackling the poor roads with more newly paved sections being completed all the time although in the short term this does create more delays and diversions because of the work being carried out.